Why "Wednesday" Doesn't Really Work

The second season of Netflix's hit dramedy is a Gothic soap opera that badly fumbles the Addams Family legacy.

Last Wednesday saw the release of the first half of the second season of Netflix’s Wednesday, the dark and rather violent take on the Addams Family from the creative workshop of Tim Burton. I enjoy the series for what it is, a supernatural Gothic dramedy in Burton’s signature macabre style (he directed episodes 1 and 4 in this batch), but as an Addams Family story, it isn’t just a failure but almost actively unpleasant. This is no knock on Jenna Ortega, whose deadpan performance as the title Addams is rightly praised, but I must object to the premise of Wednesday as an Addams Family tale.

Of course, there are the usual caveats: The Addams Family are fictional characters, so they can be reconfigured and rewritten in any way the rightsholders choose. I am not debating their right to make this show in this way, only whether I liked it.

Wednesday inhabits a conceit that is very different from any of the previous versions of the Addams Family. Set in a world divided between everyday humans (“normies”) and a demimonde of superpowered mutants and monsters (“outcasts”), the story takes place at a school for the supernaturally gifted and takes the form of a (sometimes quite grisly) murder mystery. In the first season, the action focused primarily on Wednesday, which masked some of the departures from older Addams Family adaptations a bit.

This season, the whole Family joins Wednesday, and this makes increasingly and painfully obvious how fully the show either does not understand the appeal of the Addams Family or intentionally treats six decades of characterization with contempt. So divorced is Wednesday from the Addams Family in its many earlier forms, and so generic in its Gothic trappings, that you could substitute almost any other set of macabre characters for the Addams clan in Wednesday and still have the same story. It could equally well be about Eddie Munster going off to boarding school, or the vampires from Twilight, or any of the countless CW or Netflix supernatural teen dramas that came and went in the 2010s.

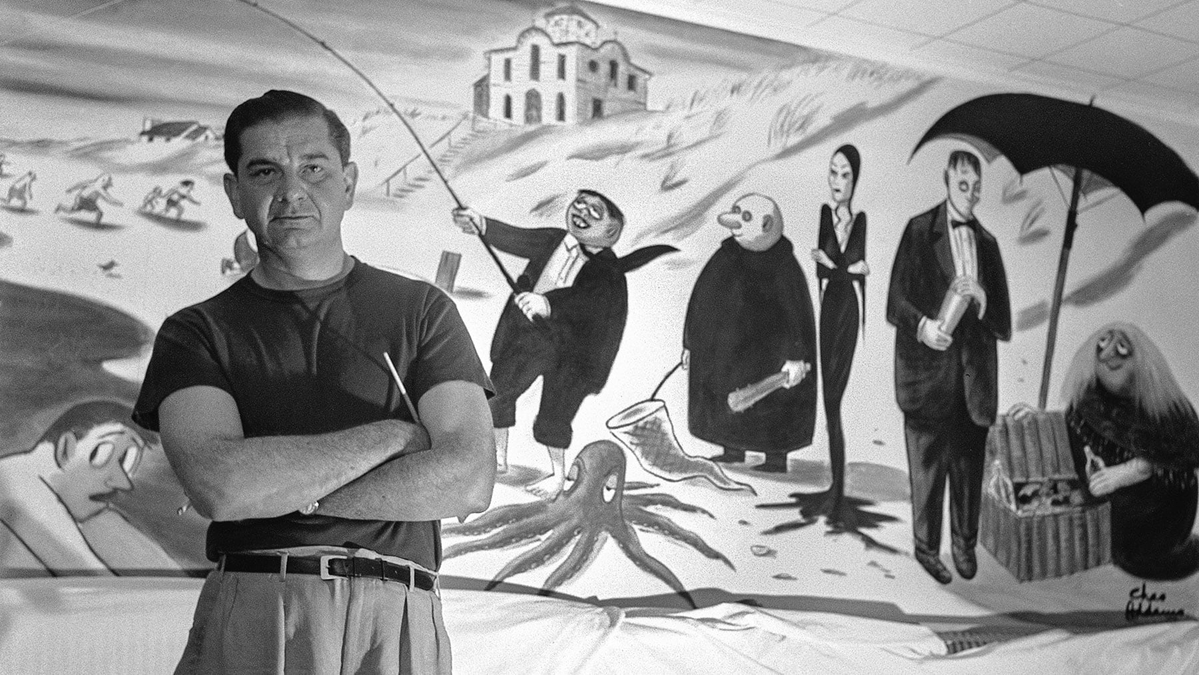

The Addams Family originated with the justly famous series of 150 single-panel cartoons that Charles Addams drew for The New Yorker between 1938 and 1988. These cartoons made ample use of Addams’s sardonic wit and macabre humor, depicting the Family as sinister ghouls who delight in inflicting pain on conformist, conventional small-town Americans. Addams’s cartoons presented the Family as predatory remnants of the prewar aristocracy—morbid, yes, but distinct from middle-class society around them, something Wednesday downplays by making the supernatural so prominent and the Family relatively “normal” in their “outsider” culture, among whom they stand as revered elites.

Charles Addams did not define the Family for many years, and in the earliest cartoons the separate ghouls did not even appear together. Most of what we think of as “The Addams Family” is the result of the collaboration between Charles Addams and the team of David Levy and Nat Perrin during the creation of the Addams Family television adaptation. It was in the creation of the show that Addams named his characters (except for Morticia and Wednesday, whom he had previously named for a set of dolls) and defined their personalities. Levy added Cousin Itt, and the TV team changed Thing into a disembodied hand. Similarly, while Addams never decided in his cartoons whether the Family were wealthy eccentrics or impoverished degenerates, Levy made them fabulously wealthy and connected them to the Spanish aristocracy and old New England stock.

Addams himself ran hot and cold on the sitcom (he found the characters insufficiently “evil”), but it established most of the lore now associated with the Addams Family, and it more clearly presented the family as a satire of eccentric Victorian and Edwardian moneyed elites, who by this point were a nostalgic memory. Both the cartoons and the sitcom emphasized the trappings of prewar old money: their decaying Victorian mansion and its elaborately carved furniture, their exotic colonial interests, their morbid fascination with death, and their love of tradition, etc. The unfashionable clothes they Family wear are exaggerated parodies of Victorian and Edwardian outfits.

In the postwar years, everything associated with the elites of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had been discredited by the two wars and the Depression. Most of the great families had lost their fabulous wealth or saw it divided among multiple dissolute heirs. The grand houses of the nineteenth century had fallen into decay, were subdivided into apartments, or had been bulldozed in misguided “urban renewal.” Victorian furniture piled up in landfills under the withering minimalism of midcentury modern design. It was easy to see the old world as something to satirize as decayed, morbid, and the antithesis of everything supposedly upright and good about 1960s America. The most common plot on the sitcom was good old postwar middle-class folk discovering that the idle old money rich were too weird for their beige suburban lives and fleeing in terror when confronted with their nonconformism. The show took pains to make the family eccentric but not, as Addams had done, evil.

I have my own bias here. The 1964-1966 Addams Family sitcom was a bit part of my childhood, and one of the most memorable reruns I would catch on random New York “superstations” in the days when we only had thirteen channels in my small town’s very basic cable system. I can distinctly remember watching the sitcom on the small 13-inch television in the kitchen in the evenings when my parents were watching Wheel of Fortune in the living room. It was one of my favorite reruns—along with Batman, Green Acres, F-Troop, and Get Smart (apparently my taste has always run a bit toward camp)—and so I tend to see that version of the Addams Family as more or less the standard.

And most later adapters of the Addams Family had the same bias. The 1973 cartoon series, the 1992 cartoon series, the 1998 Fox Family Channel live-action series, and the various cartoons of more recent years have built out from the 1964 sitcom’s foundations. Many of the adaptations from the 1970s through the 1990s even featured cast members from the 1964 show. In all of these versions, whatever changes they made, the basic notion that the Addams Family represented the vanished old-money aristocracy persisted.

The two 1990s Addams Family movies, The Addams Family (1991) and Addams Family Values (1993), while restoring some of Charles Addams’s bite, leaned even harder into the Family as Grey Gardens-style decayed old-money elites. Even more than in 1964, this Addams Family was fantastically wealthy but insular and decadent, rotting away from idleness and wealth. The first film revolved around an effort to seize control of the Addams Family wealth, temporarily dispossessing Gomez and Morticia, who cannot handle working-class life, while the second film starkly contrasts the Addams Family’s old-money elitism with the gauche nouveau-riche taste of Fester’s bride, who, of course, is after the Family’s money.

By contrast, Wednesday sees the Addams Family as just a node in a whole society of “outcasts” in a supernatural world of wealth and privilege, which robs the characters of their power. Certainly, the 1990s movies presented a much larger extended Addams clan than previous versions, but they were never shown as more than a small, largely unseen group of wealthy elites. Wednesday blows this idea beyond all proportion and does so with a largely straight face. Morticia and Gomez, especially, are played so humorlessly as to essentially be the people they were first intended to parody. Without the satire and comedy, a dramatic Addams Family becomes just another Gothic soap.

Wednesday makes magic and the macabre simply a lifestyle choice within a particular culture, and the symbolism shifts from social class to genetics, in keeping with our increasing immobile, DNA-centric social order. The “outcasts” are genetically possessed of supernatural powers, which set them apart from society and make them the subject of fear and hate. The choice to make the Addams Family Latino instead of hailing from Old World Spanish heritage emphasizes the incomplete way Wednesday, intentionally or not, has incompletely shifted the allegory from social class to race and genetic determinism. The message is not, as it had been in past versions, to be true to your own tastes, loves, and interests, but rather to pledge allegiance to your genetically assigned heritage.

The previous versions, the Family’s morbidity and fascination with death and decay were symptomatic of the old aristocracy’s crumbling social status and decadence rather than as a marker of a genetically based ethnic culture. The subtext, so to speak, was actually text. But we also see a difference between Charles Addams and his TV and movie successors. Addams quite clearly held those old elites in contempt, but the later versions softened the stance as nostalgia for the world before the wars took hold and the Victorian period—hated since Lytton Strachey danced on its grave in 1918—underwent a series of reassessments that restored its reputation. In Wednesday, the change is complete, and there is basically no difference between the Addams Family and the “normies” except the differences you’d see between any two cultures.

That reassessment of the Victorian era contributes to the reason that Addams Family adaptations have largely failed to work since the 1990s. We are more like the Addams Family today than we are the stolid midcentury middle-class who screamed in holy terror at the idea of eating food with spice. The Addams Family, in their canonical form, protected wetlands (swamps), preserved antiques, enjoyed authentic world cuisine, read international literature, befriended people from a wide array of global cultures, and even practiced yoga (“Zen yogi”)—all practices that horrified white America in 1964 but are completely normal today.

The Addams Family of Wednesday had to become cruder, more violent, and more grotesque to achieve the level of shock, which tells you all you need to know about our degraded age.