Don't Ask, Don't Tell

The strange story of how a bad book pushed James Dean back into the posthumous closet.

Last week, a Hollywood trade publication passed along an announcement from a Los Angeles literary agency that an Emmy-nominated TV producer had begun scripting an adaptation of Surviving James Dean, a 2006 memoir by the late TV writer William Bast chronicling his stormy friendship and sort-of romance with Dean, along with Dean’s various same-sex relationships. That such a project is still something of a shock fascinates me because it wouldn’t have been as much of one forty years ago as it is today. I am always interested in how narratives take hold and take shape, so I can’t help but be interested in the process of how what was, for a time, a well-known story has become a secret again, or, more bluntly, how big money stuffed James Dean back into the closet.

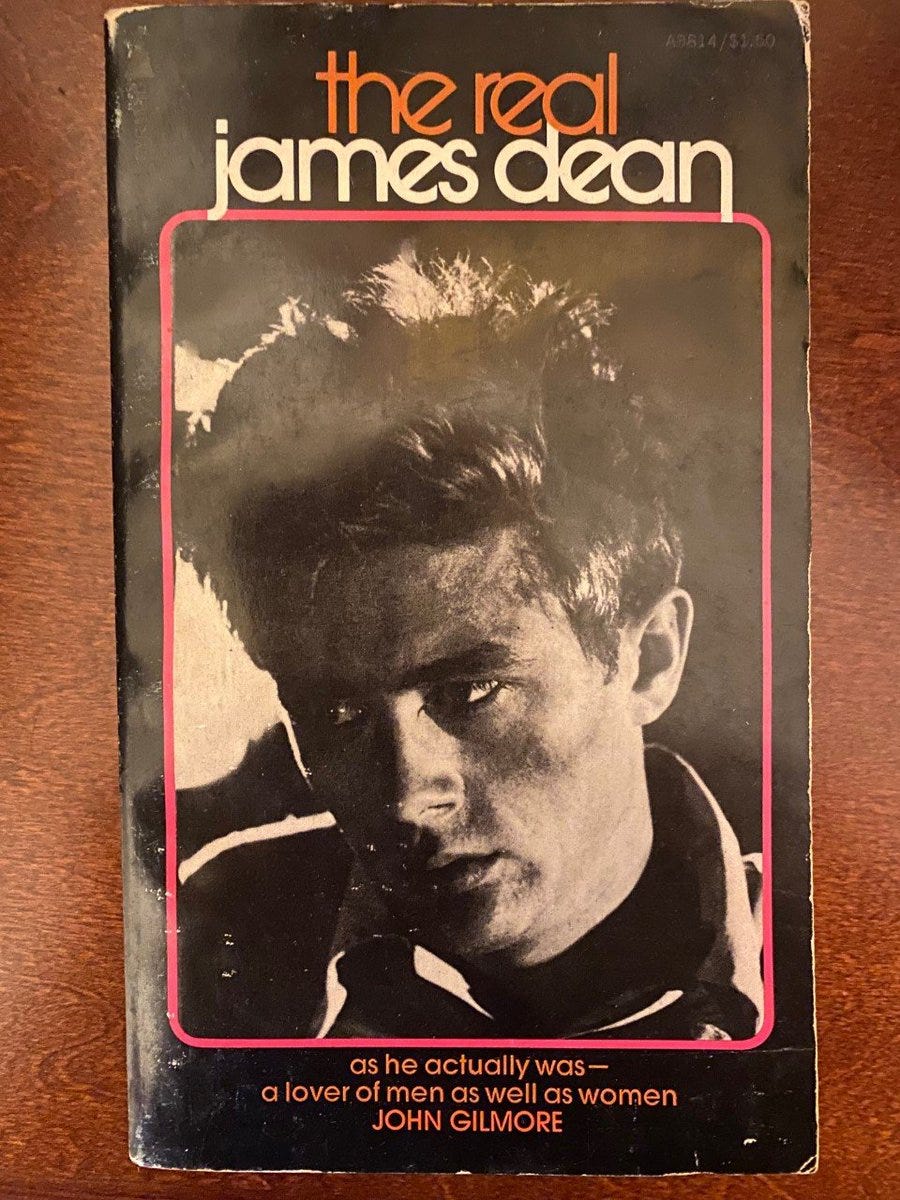

Rumors about Dean’s sexuality already circulated in his own lifetime, and scattered hints appeared in tabloid magazines, novels, and biographies in the years after his 1955 death. However, due to the tenor of the age and the Warner Bros. publicity department, it wasn’t the kind of thing discussed in polite circles. By the 1970s, however, writers had become remarkably frank about discussing it. Gay publications simply stated it outright. “James Dean was a homosexual,” Gay News wrote in 1975. Mainstream media were not far behind. Ronald Martinetti’s 1975 Dean biography featured a lengthy interview with Dean’s first (known) male lover and asked on the cover, “Was he a closet homosexual?” Venable Herndon’s 1974 biography, with cooperation from Warner Bros. and Dean’s onetime friends, depicted him as an S&M male prostitute trolling gay leather bars. John Gilmore’s 1975 biography The Real James Dean claimed on its cover to present Dean “as he actually was—a lover of men as well as women.” William Bast’s 1976 James Dean NBC-TV movie included a remarkably frank scene in which Dean talks about sexually experimenting with men and encourages Bast to go to a gay bar.

The stories were accepted well enough that when Kenneth Anger published his scandal sequel Hollywood Babylon II in 1984, its claim that Dean was a gay masochist immediately entered pop culture lore, and shortly after, the Goo Goo Dolls could write a fairly blunt and homophobic song about Dean:

Yeah I think about all the really cool things I could do and say

Then you go and tell me that you found out Dean was gay...No, I don’t want to be James Dean

I don't want to be James Dean

I don't want to be James Dean

Anymore

It wasn’t pretty, and reflected the time period, but one way or another a lot of media were fairly direct in addressing Dean’s sexuality. And then something changed that made this directness impossible.

What changed was money. In the 1980s, Dean’s heirs incorporated his estate in order to exercise trademark control over his intellectual property, and they turned administration of the company over to a professional management firm, Curtis Management Group. In the early 1990s, the Dean estate won a court battle with Warner Bros. over control of Dean’s name and image. Under the precedent the case set, celebrities’ heirs, not movie studios, owned a star’s image. The Dean estate secured control over most existing photos of Dean (I’m not exactly sure how—they don’t seem to own the copyrights), and in short order, producing any project about Dean de facto required CMG’s permission. That meant Christmas ornaments, cookie jars, cologne, and porcelain snow globes were in and anything that seemed controversial was out.

The real crisis point came in the early 1990s when journalist Paul Alexander began work on a Dean biography ahead of the fortieth anniversary of Dean’s death. Alexander secured cooperation from the Dean estate, CMG, and Dean’s heir and cousin, Marcus Winslow, Jr. They thought Alexander was writing a standard biography. Instead, his 1994 book Boulevard of Broken Dreams was a wildly miscalculated effort to repackage the 1970s revelations for the Hard Copy tabloid era. Where earlier books treated homosexuality with a suspicious remove, Alexander reveled in pornographic detail in what was billed as the first ever sexual biography of Dean. No, seriously, it’s porn: “Carefully Jimmy positioned himself on top of Jonathan. Jimmy spit in the palm of his hand before he rubbed the saliva on his cock. Gently he wedged his cock between the cheeks of Jonathan’s ass….”

In Alexander’s mind, this was an important way of saving the real James Dean from vanishing beneath the barrage of tchotchkes, t-shirts, and posters sold in his name. (He even describes Dean’s sexual frustration as a “more poignant tragedy” than his death.) But Alexander misjudged the moment. This was the tail end of the AIDS era, the time of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” when homosexuality was still a stigma and most Americans professed disgust at gay sex. Instead of imbuing his subject with grace and dignity, he turned Dean’s sexual explorations into freak shows for readers’ horrified titillation. His reliance on 1960s Freudian psychology—parental problems turn boys gay—didn’t help.

Reviews were terrible, and not a little homophobic. “Cheap exploitation!” said one newspaper. Alexander “assume[s] the worst” by suggesting Dean was gay, said another. The New York Times assigned feminist writer Molly Haskell to trash the book, correctly noting that it was mostly Venable Herndon’s facts mixed with “pornography.” Haskell unpleasantly praised past generations for refusing to talk about gay sex before declaring the subject moot because everyone is a little gay, and anyway, staying in the closet let Dean “keep himself in sports cars” and paychecks, so could it have been that bad? Yes, this was what feminism looked like in the 1990s.

William Bast sued Alexander for libel and demanded Penguin stop publishing the book, denying Alexander’s claim he and Dean were lovers, a position he recanted when he decided in the 2000s to stop “protecting” Dean’s reputation from homosexual accusations.

Dean’s cousin and the management team considered the book a “betrayal,” according to anthropologist James Hopgood, who spoke to them shortly after its publication. And they didn’t let it happen again. Marcus Winslow was adamant Dean had been straight and refused to cooperate with any project that said otherwise. In short order, virtually every movie, TV show, or documentary about Dean, from PBS’s American Masters to A&E’s Biography to TNT’s James Dean biopic to the big screen Life went silent on the issue of sex to secure access to the Dean estate’s resources. (Life was reported to have made script cuts in exchange for props.) Even book authors backed off, downplaying the issue in order to get access to archival materials and photographs. Meanwhile, publishers pulled earlier books from print. When William Bast finally published Surviving James Dean in 2006, it was with an obscure small press, in limited run, illustrated primarily with Bast’s own personal archival material.

Meanwhile, scholarship has largely ignored the role of the Dean estate in shaping perceptions. Academics speak of “eras” of interpreting Dean’s sexuality, including the “gay” era of the 1970s and the “bisexual” era of the 1990s in order to suggest the real person is an unknowable cypher. Such claims of an uncertain, unknowable past support particular interests by generating clashing ideas without considering the impossibility of imposing finely grained contemporary sexual identities onto the 1950s, when “homosexuality” didn’t simply mean “gay” as we think of it today but referred to virtually any LGBTQ+ identity—and without considering how those interpretations change as the balance of money and power tip movies and even books toward particular points of view.

In short, as far as the general public is concerned, outside of the LGBTQ+ community, money and power effectively pushed Dean back into the closet.

Once again, an excellent overview of one of the most contested issues of Dean's legacy. It would be nice if there was more effort applied to his place in the history of dramatic arts and his personal journey as a self-described artist.

What I personally await is your considered opinion of he whole matter of his precise sexual makeup. Not just a clinical diagnosis of straight, gay, or bisexual, but how he used his attractiveness & charisma to further his career and relationships.

I dunno…… from both sides of the coin, It seems very easy to write about someone who’s been gone for such a long time….. and, of course, everyone is an expert.