"It Shocks in a Staggering Fashion"

Inside the surprising and rare 1962 James Dean biography that labeled Dean a "bisexual psychopath."

“It shocks in a staggering fashion”—or so said the publisher of Rebel, poet Royston Ellis’s 1962 biography of James Dean, and the first to report his homosexual encounters.

I was deeply disappointed to discover that Ellis died last month, four weeks before I finally got a copy of Rebel. It’s a shame because after reading the deeply strange book, the last important book about Dean I had not yet read, I have questions I wish I could have asked him. Notably, I really want to know how he managed to produce a full, and mostly accurate, account of James Dean’s same-sex relations a full decade before anyone else, all without apparently doing any original research.

Ellis’s book is extremely rare and difficult to obtain. Although it is listed in the bibliographies of several James Dean biographies, none betrays any knowledge of its contents beyond a single phrase, calling Dean a “bisexual psychopath.” Only one book, a decades-old academic study of gay audiences and their parasocial relationships with celebrities, mentions anything of the book’s contents, and even then knows it only secondhand.

So, even though I can’t answer all of the questions I have about Ellis’s account, it seems worth writing something about it for the historical record, if only to save future researchers effort.

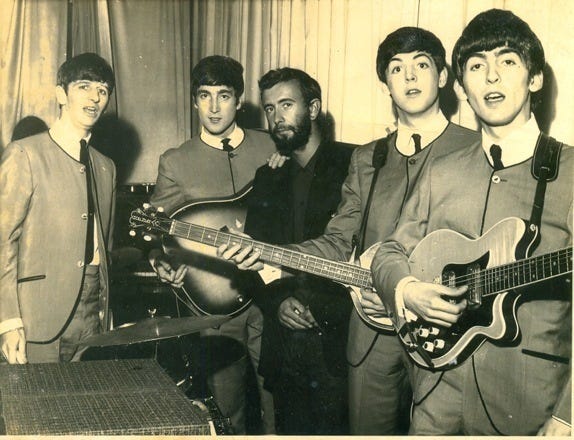

Royston Ellis was 21 years old at the time that he wrote Rebel, having come to prominence as a teenaged Beat poet. He was a friend of the Beatles, and in time would inspire their song “Paperback Writer.” In 1962, however, he coming off the success of a book he published the previous year on pop music and took for his next subject the icon who had inspired both the Beats and the Beatles.

Rebel is not a good book. Instead of writing a traditional chronological biography, Ellis instead produced a thematic biography, with four ill-defined chapters organized into irregular sections by character trait. It’s unusual, but also confusing, obscuring the chronology of Dean’s life in order to blend the whole of it into an undifferentiated mass. Ellis is also a hypocrite. Ellis’s opening passage (prefaced by his own poetry) delivers a lengthy diatribe about the contradictory “facts” about James Dean reported in the fan magazines and gossip rags, and claiming that the “Hollywood-manufactured swaddling clothes can be torn from filmdom’s illegitimate son” to uncover the real man beneath Warner Brothers’ publicity campaign.

That sounds nice, but Ellis’s books is, with the exception of two sections of one chapter, entirely composed of summaries of the very fan magazine and gossip rag stories about James Dean he claims to despise, repeated uncritically, with no effort at resolving contradictions that Ellis’s fractured chronology renders invisible. Indeed, when he attempts to be critical, he is wrong. He asserts that Dean was not moody as magazines claimed, but was quite happy. Dean’s private letters are filled with laments about loneliness, depression, and wanting to die. Ellis cites no sources other that William Bast’s 1956 biography of Dean, but the quotations he uses are identifiable, and his close paraphrasing of the articles he uses rendered his sources immediately recognizable to me, since I have read them all, too.

And so, stipulating that nothing original can be found in all but one chapter of Ellis’s book and his only contribution to his sequential summaries is to glue them together with some insufferable existentialist / Beat analysis, section VI of chapter 3, “Girls,” and VII, “Sex,” are all the more surprising.

“Girls,” is a largely standard account of Dean’s reported relationships with various starlets. The stories are copied from fan magazines, with Ellis expressing no concern about how much of this material was simply P.R. He does conclude—remarkably, since this was not otherwise reported in print prior to the middle 1970s—that James Dean had no interest in sex with women, primarily engaging in sex with women as a way of securing their companionship. “Frankly, he just wasn’t interested,” Ellis wrote.

However, the section contains some material that cannot have come from his magazine sources. He relates a clearly fictitious story of Dean losing his virginity to a girl who forced herself onto him at the county fair. Ellis—and how would anyone know this?—claims Dean was “disgusted” by the sex and traumatized when he discovered the girl shared his mother’s name, thus perverting his heterosexual sexual development. I have been unable to find a source for this anecdote.

Ellis also tells a story of how a much older woman, nearly twice Dean’s age, had seduced him, taught him about sex, and tried to forge a permanent relationship with him, from which he fled, too young to commit to a lifetime together and desperate for freedom. He left this woman and quickly met a girl his own age, with whom he had a loving affair that ended when she realized he didn’t want a girlfriend but a mother. The story is most likely a distorted and gender-swapped account of Dean’s relationship with Rogers Brackett, the ad executive fifteen years Dean’s senior, whom Dean left for Liz Sheridan, though it could perhaps be a description of his allegedly sexual teenaged relationship with his teacher Bette McPherson, twelve years his senior, though few of the details otherwise align and McPherson only made the claim in the 1990s. She said it was Dean, for example, who proposed marriage, and she who said no.

He finishes the section by telling a story that Ursula Andress told about being abandoned at dinner when Dean lost interest, but he attributes it to a “dancer” named “Eileen Forhan” who appears in no other source known to me. Ellis calls Forhan the girl Dean was dating shortly before his death, with whom he had towering arguments, but that was Andress.

It’s obvious that Ellis had access to some source that isn’t known to me and left no other trace in any other writer’s account of Dean’s life. It’s also clear that this source must be tied to the subsequent “Sex” section because the “Girls” section has two irreconcilable threads, Ellis’s copying uncritically from fan magazines about Dean’s boundless heterosexual prowess (and reveling in his supposedly untiring sexual appetite) and Ellis copying from his unknown source about Dean being uninterested in heterosexual sex and primarily caring about women as a source of emotional support and companionship. Ellis makes no effort to integrate the two quite distinct sources.

The “Sex” section is even more surprising because he abandons the fan magazine sources altogether and is obviously reliant on a source that is well-informed about Dean’s homosexual encounters. Ellis knows that Dean’s fraternity brothers had concluded he was gay and bullied him as a result. Ellis correctly reports that Dean had homosexual encounters with powerful Hollywood men in the months after he left college, and he also correctly describes these as commencing when Dean met older gay executives while working as a parking attendant next to CBS’s studios in Los Angeles. Ellis correctly reports that while living in New York, Dean vowed never to let another director or producer take advantage of him, and he also correctly reports that following this decision, Dean’s subsequent sexual relationships were all with younger men and due to “mutual attraction.” He even states rather directly something that is only hinted at even in much later accounts, that Dean saw a psychoanalyst for help dealing with his sexual anxieties.

But Ellis also includes material that is either fictitious or garbled. He claims, for example, that in high school, “no one seemed to mind if he slept with a boy.” In reality, Dean wrote bitterly of the prejudices and hatreds in his hometown, and there is no way any homosexual activity would, if known, have been tolerated in 1940s rural Indiana. He also describes Dean regularly visiting gay bars, a claim that Rave magazine had alluded elliptically to in 1957 but is otherwise unspoken until 1974.

Ellis imposes his own meaning onto the material he received, insisting that despite “friends” claiming Dean was “exclusively homosexual,” he was a “bisexual psychopath” since his “all-consuming interest in girls” (the ones he himself said Dean had no interest in bedding!) “proved” his absolute bisexuality.

Even though Ellis was himself bisexual, he took a startlingly negative view of homosexuality and bisexuality in Rebel. He describes Dean in terms of mental illness, and he declares homosexuality an “evil.” He states that, had he lived, Dean’s “homosexual streak” would have turned him “evil,” but in backhanded compliment, he praised Dean for not “corrupting” and male youths that had not previously been “tainted” with homosexuality. It is, in places, difficult to separate the story Ellis is working from and the lengthy Freudian analysis Ellis has imposed on it, going so far as to claim that because of his “turmoil” over “women’s love” due to his mother’s death and his early bad experiences, he “tried homosexuality.” With Freudians, if it’s not one thing, it’s your mother.

Fortunately, Ellis says, Dean “was not a blatant homosexual; the kind that mince around making effeminate gestures and assuming as near as they can all the mannerisms of women. Nor was he the calculating kind who, like the male prostitute, turns queer merely for financial or career gains.” No, Dean was in it for love, Ellis says—immediately before alleging he shrewdly sold his body for financial and career gains.

Overall, it seems that Ellis was working from a fairly complete story of Dean’s sex life, which he did not really think through as he interlaced it with off-the-shelf Freudian nonsense popular in those days. But where did a 21-year-old thousands of miles from Hollywood get this account, so remarkably accurate and the only one I know of published prior to 1974?

Unique among the chapters of the book, “Sex” alludes to no sources and names no names. This suggests that the source is someone who didn’t want to be named. Had it been, for example, Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylone (1959), which describes Dean as enjoying “sex assorted with beatings, boots, belts and bondage—spiced with knowing cigarette burns (which gave Jimmy his underground nickname: The Human Ashtray),” we would expect some reference to Anger or the book. But since none of that appears in Ellis, other than a vague reference to Dean being “kinky” and enjoying “sadistic pleasure,” I doubt this is the direct source, especially since it was only available in French, and Ellis made no other use of French material.

In France, several publications discussed Dean’s homosexual relations. Yves Salgues, in James Dean ou le mal de vivre (1957), describes Dean having gay sex with a sailor who introduced him to a Broadway producer, and thus he scored his big Broadway break. The story is based in part on a darker true story but it doesn’t appear in Ellis, who uses the fan magazine sanitized version. Raymond de Becker, the Belgian pederast and writer, wrote that same year that “some circles” who claimed Dean “had homosexual relations,” an allusion paralleling Ellis’s claim that “some people who knew him well” said Dean was gay. But de Becker was only aware of vague rumor.

Multiple memoirs attest that the rumors were present even while Dean lived. That they existed isn’t in question; how Ellis got such a complete and accurate version of events is. The version of events Ellis relates closely parallels that of John Gilmore, a friend and lover of Dean’s, who told virtually the same story in his several Dean biographies from 1975 onward—especially the conclusion that Dean consciously rejected old men in favor of younger lovers. Gilmore was even living in France at the time that Ellis was writing his book in the Channel Islands between England and France. But Gilmore was also a fantasist who happily recycled other people’s anecdotes as his own, so there is no way to determine whether Gilmore’s own account wasn’t influenced by Ellis. And Gilmore, for whatever it’s worth, thought Dean was straight, not gay, and just extremely curious about “gay sex.”

Another candidate for the source is William Bast, Dean’s friend, biographer, and (briefly) lover. Bast knew most of this material and had spent several years in London just before the time Ellis wrote. Bast wrote in his own 2006 memoir that the British arts community was quite familiar with rumors that Dean was gay and frequently asked him embarrassing questions about Dean’s cock size and sexual performance. He also wrote about discussing this with Colin Wilson, who had wondered if Dean fit his mold of an “Outsider” rebel, from Wilson’s famous book The Outsider (1956). Ellis thanked Wilson for his help in the acknowledgements to Rebel, though this was more likely due to Ellis cribbing the traits of an Outsider / Rebel from Wilson to apply to Dean. Bast himself was adamant about keeping Dean’s same-sex experiences secret to protect his reputation, so it seems unlikely that he blabbed so fully.

Instead, there another possible candidate. Aside from the reference to Dean’s psychoanalysis, which Ellis probably gleaned from Bast’s 1956 Dean biography, the “Sex” section’s narrative stops around early 1954. This is when Dean left New York for Hollywood, implying the source knew Dean in New York but not after. Given that timeline and the hostile nature of the description, this would suggest the source could be (directly or indirectly) one of the circle of cosmopolitan New York gay men in the arts who had facilitated Dean’s sexual abuse at the hands of producers. This circle included Dean’s estranged lover Rogers Brackett and Brackett’s friends, including producer Lemuel Ayres, composer Alec Wilder, and several others. Even the garbled or fictitious parts sound like lies that Dean had told Brackett. The narrative’s similarity to one given in Ronald Martinetti’s 1975 Dean biography, whose source was actually named as Rogers Brackett, would make one of their circle a good candidate for the source. On the other hand, they were exploitative, lecherous men, and Ellis wrote from an anti-gay perspective, so the narrative’s underlying sympathetic portrait of Dean as lovelorn and naïve would seem at odds especially with Wilder’s antipathy to Dean. It would match Brackett’s later in life views, however, as told to Martinetti.

Whoever it was, Ellis’s book is testament both to the existence among gay men of a fully developed narrative about James Dean’s homosexual sex life very early after his death and its secret transmission outside of both the mainstream and the tabloid media of the day. Why no one, in sixty years, asked after his sources is beyond me. The incuriousness astounds me.

Royston Ellis was bisexual, not gay or homosexual. Please correct this. It was well known that James Dean was bisexual and Sal Mineo was bisexual as well.

Come boys and girls back then bi ment gay cause you couldn’t admit you’re gay.