James Dean, Queerness, and the Problem of Overstatement

A Substack essay claims James Dean lived openly as a gay man, but the truth is more complex.

Earlier this week, “Wendy the Druid” posted a lengthy piece on Substack reflecting on James Dean’s sexuality and its relevance to our attitudes about sexuality, sex, and gender today. Wendy’s piece draws on my book, Jimmy: The Secret Life of James Dean, and it’s much more direct in the conclusions it draws than I was in my book. I appreciate the sentiment, and much of what Wendy writes is heartfelt and meaningful. As I write in my book, there is immense value in understanding Dean’s struggles as a queer man, and his story can be, by turns, inspirational and cautionary for queer youth today. But I would be remiss if I did not point out that the author has vastly overstated the case and has made James Dean seem like much more of a queer activist than he ever was in real life.

Much of what Wendy writes is undoubtedly correct, particularly the line connecting James Dean’s experiences as a queer man and his embrace on a less traditional version of masculinity that was connected to emotional expression and vulnerability:

But here's where Dean's story becomes something that should make every LGBTQIA+ person's heart pound with recognition: he didn't let that early trauma turn him into another emotionally dead American male. Instead, he embraced the very sensitivity and vulnerability that his father couldn't handle, turning his wounds into weapons against a society that demanded men be robots.

The author is also completely correct about the way that Dean’s experiences as a queer man navigating a hostile world informed his acting choices and helped to develop the sensitive but rebellious persona that audiences reacted so strongly to, though it might be stretch to describe them as “queer coded.” However, the author has vastly overstated the degree to which Dean openly embraced his feelings for men:

His relationship with Rogers Brackett wasn't some dirty secret to be whispered about in dark corners—it was a genuine partnership that combined love, mentorship, and mutual support. Brackett, a radio director and advertising executive, recognized Dean's talent and helped launch his career, but more importantly, he provided the kind of emotional intimacy that straight couples took for granted while queer people had to hide in shadows. The relationship was documented not through gossip but through letters, photographs, and the testimony of people who knew them both.

What makes this relationship historically significant isn't just that it happened—it's that Dean refused to treat it as shameful. In an era when gay men were expected to hate themselves, to view their desires as sickness or sin, Dean approached his relationships with men as natural extensions of his emotional and physical needs. This wasn't confusion or experimentation; this was a sophisticated understanding of human desire that was decades ahead of its time.

I quote this at length because there is so much in there that seems superficially correct but is in fact unsupported by evidence. To take it from the top: There is no evidence James Dean spoke openly to anyone about his relationship with Rogers Brackett. Both William Bast and Liz Sheridan knew about it, but both received only partial information, which contradicted, in different ways, what Brackett himself said. Dean also told Vivian Matalon about Brackett, but Matalon’s recollection was that it was in negative terms. Dean described Brackett only as a roommate to his first agent. He must have spoken more honestly with his later agent Jane Deacy, as she was in direct contact with Brackett and wrote to Dean about him, but the nature of those conversations is not recorded. The best evidence we have is that Dean, after an initial few months of infatuation with Brackett, soured on the relationship and, as Brackett’s friend Alec Wilder and Bast both independently recorded, Dean had come to see it as exploitative or even abusive.

While there is testimony from people who knew them both, such claims are often dismissed as gossip. There are no surviving photographs of the two men together, and the only surviving contemporary evidence of their relationship are the papers associated with the lawsuit Brackett filed against Dean to try to claw back money Brackett had spent on Dean during their relationship. These were not personal letters—while the existence of personal correspondence and memoranda is implied the papers, both Bast and Dean biographer Joe Hyams wrote that any papers implying homosexuality were destroyed after Dean’s death.

I’m not sure it’s fair to say that Dean did not treat his relationship with Brackett as shameful. That really depends on the time we are talking about. From the time he met Brackett in 1951 until the end of their relationship at the end of 1952, we can say that he did not treat it as shameful within the queer community that he and Brackett operated in. Afterward, however, he took great pains to remove Brackett from his life story, and even before that he at least pretended to be ashamed when discussing it with Liz Sheridan.

Wendy also states that Dean had a physical relationship with composer Leonard Rosenman, but there is no evidence whatsoever of this. Rosenman, who was straight, rather pointedly stated on multiple occasions that he had never seen any evidence that Dean had same-sex relationships.

To that end, the author’s claim that Dean was living openly as a gay man is also far too overstated:

Into this environment of state-sanctioned terror walked James Dean, refusing to perform the kind of elaborate heterosexual charade that other actors accepted as the price of fame. His openness about his relationships with men, his refusal to enter into publicity marriages, his insistence on living authentically despite enormous personal and professional risks—all of this represented a form of courage that bordered on the suicidal.

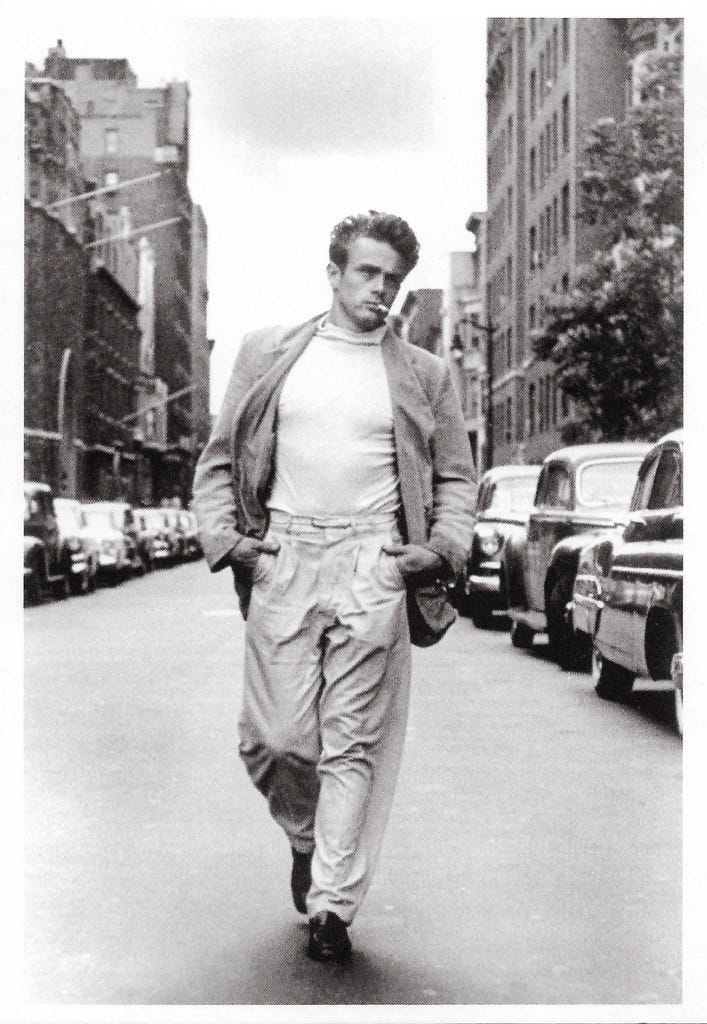

Some writers have suggested that during his New York years Dean was living more or less as an openly gay man, but that was never fully true. He was certainly a part of Brackett’s gay circle and, as the existence of later rumors testified, known in theatrical circles for it. But during that time, he rather famously had a lengthy relationship with Liz Sheridan (even while seeing Brackett behind her back) and took pains to present himself to his colleagues as heterosexual. Martin Landau, for instance, knew Dean in New York and recalled Dean talking incessantly about women, to the point he became convinced for the rest of his life that Dean was completely straight. By the end of his time in New York, likely in response to a then-current media panic about “swishes” in the TV industry and “perverts” on Broadway, Dean began dating multiple women to create the public image of a womanizer.

It's also not true at all that Dean refused marriage. He is on record as having proposed to five different women, most of whom he had known for only weeks or months, and I personally own the letter from his agent providing the only contemporary proof that he had planned to ask the starlet Pier Angeli to marry him, if he could work out how it would affect his draft exemption for homosexuality. Now, technically, none of the five attempted proposals were “publicity marriages” in that they were not arranged by an agent or studio, but it is nevertheless clear from statements he made to his insurance agent Lew Bracker that Dean viewed marriage as an obligation to his career he would need to undertake sooner rather than later.

At the end of is life, he seemed to reverse course, as he did on so many things, telling a magazine that he wouldn’t marry until at least the age of thirty. This was at the same time that Dean told William Bast that the two men should live together, with the implication Bast felt that it would be as a couple.

In Jimmy, I use these events, and Bast’s statement a year later to Colin Wilson that Dean had come to accept his sexuality, to tie together Dean’s journey and give a bit of a grace note to what had been his deeply ambiguous and conflicted feelings about sex and love. There is no way, as Wendy wrote, that Dean, had he lived, would have lived “more openly” or “use[d] his platform to challenge the very systems that oppressed queer people,” at least not in the immediate future of the 1950s. Indeed, Dean had some rather politically incorrect ideas about queerness, and he deeply disliked (at least in theory, if not always in practice) effeminate gay men, preferring masculinity. According to Bast, Dean’s dislike of Rock Hudson stemmed from the fact that Hudson was quite effeminate off-camera, and his masculinity was a false front.

With all that said, I agree completely with Wendy’s final paragraph, which echoes the way I ended my own book:

But the ultimate triumph is that his example continues to inspire people to live truthfully, love deeply, and refuse to dim their light for anyone's comfort. In a world that still needs more authentic rebels, James Dean's flame burns as bright as ever, reminding us that some truths are worth dying for—and more importantly, worth living for.

We just need to be sure that we reach such conclusions from James Dean’s real life and not the one we imagine.

Hey, I’ve started an account where I collect some out of context captions of great films in cinema history. Just wanted to share it with the cinephiles around here : https://substack.com/@pariscinema?r=1x6h4r&utm_medium=ios&utm_source=profile