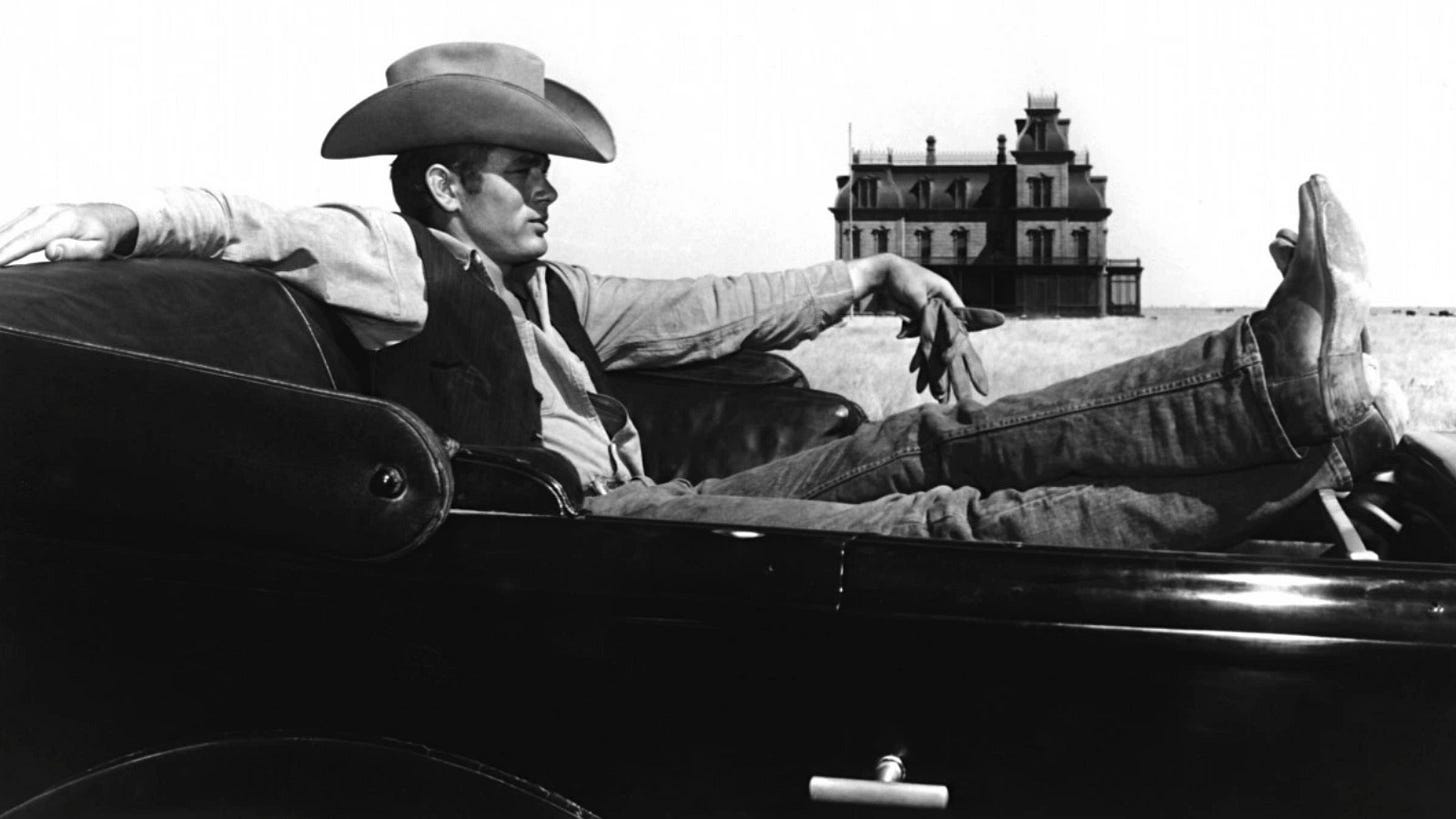

Resurrecting James Dean

An analysis of 1956 press coverage finds the fingerprints of a publicity campaign behind the promotion of paranormal and conspiracy claims.

Given my particular interest in conspiracy theories and the supernatural, I naturally have been fascinated by the various conspiracy theories that swirled around James Dean, who is the subject of the book I have been writing. One of these conspiracies alleged that Warner Bros. intentionally fabricated an urban legend that Dean had not died in the Sept. 1955 crash that killed him but instead lived on disfigured in some secret sanitarium. For nearly seven decades, writers have shrugged and passed it off as another tabloid craze. The claim of Dean’s continued life is, of course, false, and likely originated as a spontaneously generated bit teenager mythology, but it turns out there is a compelling story about how and why the media got hold of these rumors.

Interestingly, almost every book and article presents information about the media coverage of Dean’s “afterlife” out of chronological order, making it hard to see the development and patterns. That’s probably because the patterns undercut the story authors like to tell. Robert Tysl discovered as much in the 1960s when, as a doctoral student, he encountered great resistance from Warner Bros., Hollywood, the media at large, and Dean’s friends and colleagues while trying to assemble a comprehensive list (we’d call it a database today) of media coverage of Dean to track how Warner Bros. shaped his “heroic” image. Tysl’s efforts, published in his 1965 700-page (!) dissertation, help us to see what really happened.

In February 1956, Whisper magazine published a piece about Maila Nurmi, TV’s Vampira, claiming she put a black magic curse on James Dean, killing him. This kicked off a round of mainstream media coverage that focused on the morbid aspects of the growing Dean cult. In the spring, Warner Bros. began sending cast and crew from Dean’s last film, Giant, to praise Dean and to talk about the devotion of his fan base, and the thousands of fans writing in about Dean. In the New York World-Telegram and Sun, William Pepe, citing a producer of Giant, claimed the letters were mostly about Dean’s Oscar loss and the upcoming release of Giant. Several columnists reported the same about the “5,000 letters” Warner Bros. received in April.

As Robert Tysl noted, some of the wildly worshipful articles that spring, particularly in fan magazines, accidentally contained quotations from outtakes and screen tests that would not be made public until 1957 or later, thus suggesting Warner Bros. was providing the copy for the fan magazines to stoke excitement for Giant—much as they had with the prewritten copy they had provided for newspapers to cover Rebel without a Cause. (I have a photocopy of their Rebel press book with these sample articles, including blank spaces for local reporters to fill in regional details.)

But then something changed. Someone at Warner Bros. apparently came to think they had gone too far in turning Dean into a cult idol rather than a commercial product.

A spate of stories came out in the run-up to the release of Giant in the summer and fall of 1956 that all gave remarkably similar variations on the same theme, that Dean’s fans were psychiatric head cases who refused to believe him dead and Dean was a nasty monster. The articles began in June 1956 with a Newsweek report and then grew to encompass dozens of major newspapers, from the New York Post and Sunday Mirror to the Florida Times Union, as well as trade magazines and gossip rags. The similarity of the pieces and their near-simultaneous publication suggests a media campaign behind the scenes, which internal evidence from the articles tends to support. I can only highlight a few key pieces here.

At almost exactly the same time that Newsweek spotlighted Dean’s death-denying fans in June 1956, fan magazines began reporting on the rumor that James Dean was not dead, when Nell Blyth of Movie Life attempted to refute the rumor that

Jim was NOT killed in that auto wreck, but he was so badly mutilated and disfigured that his family and studio decided that he should be pronounced dead to the world. Jim is instead a patient at a private sanitarium for incurables. The boy buried in Indiana is a hitchhiker whom Jim and his buddy picked up enroute.

Blyth’s piece is quite transparently stage-managed, with strangely PR-sounding counters to each negative rumor about James Dean, Giant, and “cashing in,” providing the Warner Bros. studio line and absolving anyone, preposterously, of having a financial interest in Dean. It ended by absolving Dean of being murdered for communist sympathies and with speculation about his presumed future reincarnation—a “provocative thought.”

In July, Hedda Hopper, the gossip columnist, reported seeing letters from teenagers sent to Warner Bros. in which the teens wrote “as though he were still living.” No points for guessing how she got them.

Hearst’s American Weekly national newspaper supplement on July 29, 1956 found reporter Jeanne Balch Capen’s describing “The Strange Revival of James Dean,” painting a picture of a psychotic and “growing” fanbase that refused to believe their idol dead, with references to black magic and “the fantastic rumor that Dean was not killed in the crash, but was so badly burned that his studio and family decided to tell the world that he died while he lives out his days in a sanitarium.” The opening lines, obviously based on information provided by Warner Bros. (either directly or indirectly via earlier stories), and echoing, sometimes verbatim, a United Press story from May, would be repeated in some variation dozens of times:

The actor who receives the most fan mail at Warner Brothers lot in Burbank, California, has made a total of three pictures, only two of which have been released. In the month of April alone he drew 5,000 letters.

None of this would be surprising except for the fact that his name is James Dean and he’s been dead for 10 months.

A few days later, on August 1, 1956, Variety’s Robert J. Landry, who had given Rebel without a Cause a positive review the year before, reported on the machinations behind the scenes at Warner Bros. In an article about the “Dead Star Who ‘Lives’,” Landry said that executives were concerned about the vociferous Dean fan base Capen had described:

Recognizing that the James Dean cult is nothing to trifle with and aware that this phenomenon “goes way beyond ordinary pressagentry” Warners will this week confer with outside psychologists, public relations counsel and funds-raising experts. The latter [sic] are included because of the possibility of all the James Dean fan clubs being united behind some sort of a “Foundation.”

Landry also noted, dryly, “some disturbing ‘resurrection’ and ‘reincarnation’ themes recurring in the fan mail.” At the time, Warner Bros. supposedly received some 6,000 letters per week (per Variety) or 8,000 per month (per Life) addressed to Dean. (The number somehow kept rising with each new report.) Landry printed part of one letter: “Jimmy Darling: I know you are not dead. I know you are just hiding because your face has been disfigured in the crash. Don’t hide, Jimmy. Come back. It won’t matter to me . . .”.

Unusual for a Variety article, no sources are cited in discussing the machinations inside Warner Bros. The emphasis, though, on “pressagentry” and public relations strongly indicates that Landry’s source was within the Warner press office, giving Warner Bros.’ official position, which was that they had nothing to do with Dean Mania and were “as astonished … as anybody else.”

A similar story ran in Life on Sept. 24, quoting the same letter, transparently provided by Warner Bros., with a sampling of other letters from teenagers asking for relics of Dean. Life’s Ezra Goodman was cagey about his sources, citing only “a Hollywood publicist.” Only someone in the Warner press office would have had access to the letters to tell Goodman that the majority were requests for relics or photographs, though “many” spoke of “resurrection” and “reincarnation.” Indeed, on one page (p. 88), Goodman relates information about Warner business plans, test screenings, and internal reports that could only have come from the studio press office. Goodman was sister magazine Time’s Hollywood correspondent and worked closely with studio publicists. Rival magazine Look ran an equally dismissive feature in its October 16 issue, repeating many of the same “concerns” about Dean and his fans, nearly verbatim. (Robert Tysl noted that the attack pieces were so similar as to suggest a planned campaign.)

George Stevens, the director of Giant, was also on message, doing a series of interviews where he emphasized the official Warner position that the Dean cult was “morbid nonsense.” However, despite his personal dislike for Dean, he publicly praised the dead actor to help promote the film.

“We do what we can to help,” Steve Brooks, who headed magazine publicity at Warner Bros., told a columnist—basically admitting to providing the raw materials. The New York Daily News reported that the new Dean Mania of fall 1956 was “a hoax” and that teenagers admitted to participating only because “all this started up again” with new media coverage.

A few weeks later, just as Giant hit the box office—to become not just the biggest movie of the fall but one of the dozen biggest moneymakers of all time, to that point—the January 1957 edition of The Lowdown, a sensational scandal rag, hit newsstands. Despite the cover date, it was for sale in November 1956, right at the time of Giant’s November 24 release. (My copy has the original postal delivery stamp on the cover.) In an article on “James Dean’s Torrid Love Letters,” The Lowdown quoted Dean’s friends about the disgust they felt at the “necrophiliac” worship of Dean (borrowing the quotes, uncredited, from Life) and then reporter Perry Taussig printed a selection of letters written to James Dean. They are substantively of the same kind as Life had quoted, but with less sanitizing. There is, of course, no way to know whether Taussig simply made them up, but it would seem pointless for the accompanying photograph to picture different letters than those printed if one’s goal was to fabricate letters. Similarly, fabricating letters when so many of similar content were in circulation would seem redundant. As sensational and poorly sourced as tabloids were in those days, due to stricter libel laws, they tended not to make up underlying facts. Lowdown, however, seemed to have a set of letters carefully curated to suggest Dean’s fans were desperate housewives, deluded children, and homosexual perverts—undesirables and the mentally ill.

The question, though, is who provided this selection of letters that made Dean’s fans look like a bevy of desperate malcontents, deluded naïfs, and homosexuals. Again, Taussig offers no hints, but since every other fact in the article is copied from Life, it’s clear that Taussig did no original reporting. The letters must have come as a package, and not from Dean’s friends, or else those friends would have been quoted directly, not in mimeograph from Life.

The next month, Inside Story, another tabloid scandal rag, published an article on “The Amazing James Dean Hoax,” repeating and expanding on the Variety article from August. This time, though, reporter Lisette Dufy quoted an unnamed studio executive as claiming Warner Bros. orchestrated Dean Mania to ensure Giant became profitable, bypassing their own publicity department and using an outside firm months earlier than Variety had indicated.

But, at the same time, a high-priced, independent public relations expert was secretly hired to plan and promote the program with every gimmick he could dream up.

Warners’ executives decided that if their own studio publicity department were put to work to “revive” Dean, news of what they were doing would leak to columnists and trade reporters. In turn, these columnists would denounce the studio for commercializing a corpse.

According to Dufy, the P.R. consultant planted the rumors that Dean was still alive. (Dufy’s report inspired Robert Bloch to write a short story about a similar conspiracy, later adapted as an episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents.)

Dufy quoted some of the same letters printed in Life and other publications, and some facts lifted from Look, Life, and/or American Weekly, but then offered this interesting tidbit:

When the mail began arriving, Warners’ press department showed the letters to various Hollywood columnists who immediately reported these letters to be “sincere and genuine.” Every time a columnist printed something about the volume of letters coming in, more impressionable teen-agers wrote more letters.

Inside Story meant to cast aspersions on this, suggesting that teens had been manipulated into writing, but the salient point is that the Warner Bros. press office was behind the dissemination of these letters. When you strip out the material copied from other magazines, what remains is an interview with someone described only as “a top-flight motion picture executive,” and one privy to Warner secrets.

The article’s effort to absolve the Warner Bros. press department of responsibility while laying the blame on higher-ups and outside consultants is suggestive, but it wouldn’t mean much if not for a strange novel published a year later. Walter Ross’s The Immortal was a poison-pen letter to James Dean and to Warner Bros., very thinly disguised. The novel attacked Dean Mania and the Dean cult as well as the studio system that excused and exploited what Ross saw as a degenerate, sociopathic monster driven to madness by the evils of homosexuality, a monster that the studio had to destroy in death to protect the youth. He has a studio official write:

We have exploited his delinquency, at the same time made a hero of him, S.O.P.; but when [the] image we create becomes a cult, and cult glorifies self-destruction, or general destructiveness and antisocial attitudes, it is to [the] best interests of juveniles, audience and studio to destroy or change the image.

The reviewer for One: The Homosexual Magazine was especially perceptive in seeing how Ross’s distaste for Dean’s sexuality colored his character assassination: “The traits about him that seemed good in the eyes of others are obliterated; every intention is made to seem dishonorable, and his attractions for others placed on the level of a modern Svengali,” he wrote, adding that the book was virtually a case study for Edmund Bergler, the psychiatrist who thought gays were perverted masochists.

The 1958 novel was a best-seller and almost became a movie, but it was rumored that Warner Bros. impressed on MGM the importance of canceling the project. Ross then wrote a second, equally vicious novel, Behind the Screen, attacking what he saw as a culture of corruption at a studio modeled closely on Warner Bros.

This wouldn’t seem directly relevant, but the media of the day were rather cagey about Ross’s identity, describing him only as a “former film flak” (Billboard) or a novelist (New York Times). At the time of publication, he was a senior publicist at BMI, the music licensing firm. However, the papers knew who he really was. As Advertising Agency reported in 1957, Ross moved to BMI from none other than Warner Bros., where the former magazine editor had been an important figure in the Warner Bros. Pictures Copy & Press Relations office. Warner later downplayed his importance, calling him only a member of their team, but he described himself as an “executive” publicist in his own PR materials. In other words, at the time that “Warners’ press department” was “showing the letters” to journalists, Ross was among those showing those letters. Warner press relations in his time was rather blunt about tamping down Dean Mania, steering reporters for mainstream publications toward negative coverage of Dean in the second half of 1956, including Look’s cover story on the “strange” and “grotesque” Dean and Esquire’s rather ugly feature on “The Apotheosis of James Dean,” the latter of which I was finally able to correct in the magazine’s pages sixty-five years later. Look’s story describes in reverent tones the concern inside Warner Bros. and is quite transparently derived from uncredited handouts from Warner’s press department, which also provided, uncredited, the Giant set photographs for the decidedly negative biographical sketch.

Since The Immortal makes plain that Ross disliked Dean personally and was apparently disgusted by the whispers of his homosexual relationships (which he knew from studio gossip years before it became public knowledge), a plausible sequence of events suggests itself. Ross encouraged Warner Bros. to spread negative stories about Dean and his fans because he considered Dean unworthy of admiration and his fans mentally ill or deluded. Warner Bros., perhaps shocked by the sometimes suicidal fanaticism they had previously stoked, told mainstream journalists that Dean-worship was uncouth and provided negative information for older audiences but also brought in outside P.R. agents to maintain interest in Dean among teens in the movie fan magazines ahead of the expensive Giant’s release. Ross disapproved mightily of the whole effort and may well have been the source leaking conspiracy theories and the most deranged Dean fan letters as he started writing his book and preparing to switch jobs. We’ll never know, of course, unless he left a paper trail somewhere.

Obviously, everyone who could confirm this is long dead, and it’s probably telling that no one thought to ask these kinds of questions when people were still around to answer them. Maybe the Warner Bros. archives has documentary evidence, but I’m afraid that, unpaid, such research is a bit beyond the limits of my interest or budget. However you slice it, the evidence is clear: News coverage changed significantly after Giant left theaters, and so much of the image of James Dean that hardened into official biography appears to have been an intentional public relations campaign that very few really questioned, even decades after its purpose had been forgotten.

Your book sounds so interesting, I'm really looking forward to reading it, for that matter your article in Esquire is one of the very best I've read on James Dean.

This is such a fantastic article. It's especially helpful in laying out the timeline and the hows/whys. I read (skimmed) Tysl's thesis before but this article made me interested in looking into it again, especially since it was the first major scholarship on Dean and the creation and deconstruction of his media image.

For your book, are you mostly focusing on James Dean and the post-death Dean cult in the 1950s with the Lavender Scare and McCarthyism and paranormal/occult trends of the time? Will it also focus on the revitalization of interests in Dean in the 1970s/1980s and later?

And speaking of the paranormal while it never reached the level of the Elvis ghostly sightings the paranormal James Dean is in books and on youtube (and I'm sure you've seen these videos and obviously know way more than I do on the topic). There are more than a few videos of mediums claiming to communicate with James Dean from across the beyond. In Roy Schatt's photo-memoir he mentioned a movie magazine hiring a medium to hypnotize Schatt to try to bring Dean back from the other side. I know that isn't something unique to James Dean of course-there are videos featuring channeling/messages with other deceased cultural icons as well, but it's interesting to see how almost 70 years after his death and the first generation of fans believed they could communicate with his spirit in Fairmount or feel his ghost on the road to Salinas --James Dean is still a subject of supra/supernatural interests.

A 700 page paper? How many pages might your book manuscript be? More to the point, does this late revelation affect your draft?