Shedding Light on "Children of the Dark"

The morally bankrupt mirror of "Rebel without a Cause" exposes the bleakness of 1950s attitudes toward sex and gender and highlights what the movie did right.

In a few weeks’ time, Warner Bros. will release a new 4K Ultra-HD Blu-Ray edition of Rebel without a Cause to celebrate the studio’s 100th anniversary. The deluxe new packaging features two of the movie’s stars, James Dean and Natalie Wood, on the slipcover, the special edition metal tin, and the exterior and interior of the box holding the discs. One thing missing from the packaging is co-star Sal Mineo, who was nominated for an Oscar for his role as Plato, alongside Wood. The omission is at one level understandable—Warner Bros. wants to foreground the most famous names, and they are simply tweaking the earlier DVD packaging—but it is also a continuation of a decades-long effort to minimize the queer character in order to recast Rebel without a Cause as a traditional teen romance.

The studio’s discomfort with the film’s themes has always been quite plain, from the falsified plot summaries the publicity department provided to film critics, to the studio’s own notes demanding changes to excise any hint of homosexuality. What they meant, however, was an elimination of any sympathetic hint. An earlier version of the film’s script had a much darker take on the same theme and, apparently, didn’t cause nearly as much concern—and was even turned into a novel, which publisher Henry Holt promoted as the real story of Rebel without a Cause.

The short version is that Rebel without a Cause when through many abortive attempts to make a movie to match the title of Robert Lindner’s psychological study of a psychopathic adolescent, whose rights Warner Bros. had bought in the 1940s, before Nicolas Ray inherited the cursed movie title in 1954 for his own juvenile delinquency film. Even Dr. Seuss took a turn at writing a script, and failed.

In late 1954, the albatross fell around the neck of Irving Shulman, the author of The Amboy Dukes and a veteran of writing about juvenile delinquents. He wrote an unsatisfactory, hyperviolent story about teen psychopaths, culminating in a shootout when a jealous boy takes the others hostage in a fit of rage over losing the boy he is obsessed with to a girl.

Shulman and Ray fought over the script, but the final straw came when Shulman picked a fight with James Dean over Dean’s Porsche. Shulman, who was Jewish, was offended that Dean planned to buy a German sportscar, and Ray fired Shulman when forced to pick between his star and his screenwriter. Shulman began working on a plan to turn his script into a novel, and he later put out the story that he had become so enamored of his novelistic vision that he voluntarily left Rebel to write it. Ray replaced Shulman with Steward Stern, who softened and humanized Shulman’s story, taking his inspiration from James Dean himself, whose life and experiences helped to inform the final story and characterizations. Dean, in turn, improvised and interpreted Sterns version to make it still more radical.

But that is a different story.

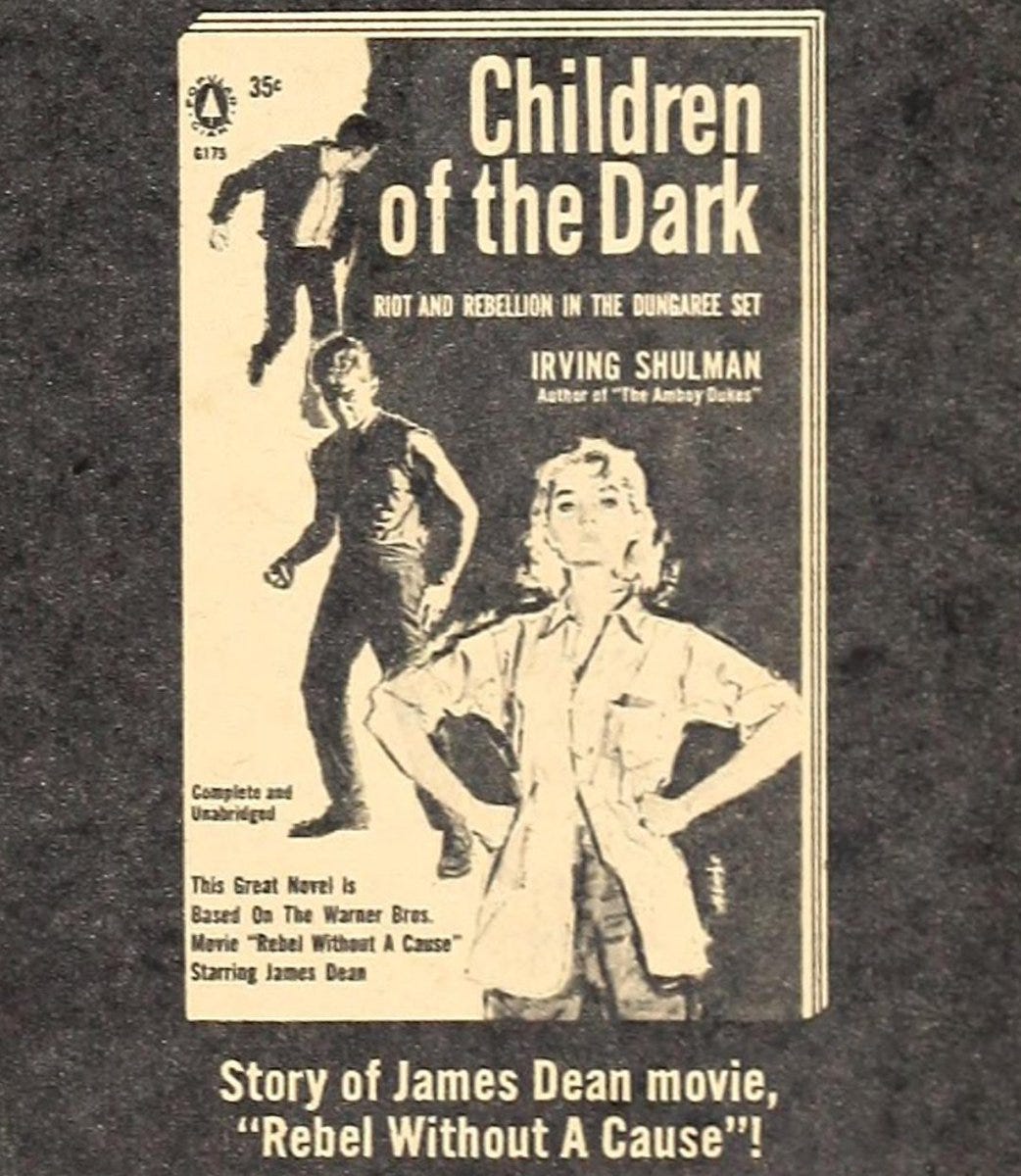

Warner Bros. gave Shulman permission to use his Rebel script for his novel, which was published in January 1956 as Children of the Dark, later subtitled Riot and Rebellion in the Dungaree Set, and advertised, with some irony, as the “Story of [the] James Dean movie, ‘Rebel without a Cause’!” Apparently, even with Dean’s name splashed on the cover of the paperback edition, fans weren’t fooled. With few—and bad—reviews in the press and apparently low sales, the book quickly faded into obscurity. It is however a fascinating mirror of the dark, morally bankrupt version of Rebel without a Cause Shulman wanted to bring to the screen.

Children of the Dark follows the rough outline of Rebel without a Cause, as you might expect. After some initial setup, the story opens with the James Dean character—here named Steve Stark instead of Jim, though transparently inspired by Dean, and informed by Shulman’s dislike for him—arriving in town as the new kid and struggling to fit in. Similar to the movie, the students attend a show at the local planetarium and end up passing the time by staging a “chickie run” in which two boys drive stolen cars off a cliff. Unlike the movie, Steve/Jim isn’t involved in this race. Instead, Buzzy (the movie’s Buzz) and a throwaway charactered called Chuck drive, and Chuck dies, leading the other kids to conspire to cover up their involvement.

Thus, two-thirds of the movie’s action takes place in the first few dozen pages of the novel, which then proceeds to do little of interest for the next 150 pages. The differences between Shulman’s version and the movie, however, are rather stark, if you will pardon the pun. Shulman’s characters are much darker than their cinematic counterparts. Steve is almost entirely passive, and rather dim. He wanders through the story as a knockoff Holden Caufield, torn between childish fantasies and adult urges, including a bizarre scene where the sixteen-year-old falls into trouble at a strip club when he doesn’t realize the stripper isn’t actually into him and that he was supposed to pay for her drinks. Steve does nothing active in the book and exists only as an object of desire—for Judy and Plato.

The Judy of the novel is a scheming manipulator and a representation of the novel’s very negative view of women. Steve’s father delivers a multi-page speech about women not being real human beings and, in fact, evil. Steve has his doubts before the novel confirms that his father’s speech is in fact true, and Steve accepts the truth. Every woman, from Steve’s henpecking mother to Plato’s absent mother to the witchy Judy, represent the kind of evil that brings men down.

But the most radical difference is in the character of Richard “Plato” Crawford, who is an unmitigated homosexual psychopath in Shulman’s telling. His Plato is the most brilliant boy in school, slight of build, bespectacled, possessed of a photographic memory, a voracious reader of books, bullied by his peers, neglected by parents, and lonely. Therefore, he is also an evil homosexual hell-bent on violent revenge. In Children of the Dark, he is gradually revealed (in a twist early reviewers complained was unmotivated and badly handled) to be the puppet-master behind the novel’s events, pushing the characters into escalating violence after he becomes fatally obsessed with Steve. Shulman, interestingly, never uses the word “homosexual” or “gay” and officially insists that Plato is motivated solely by a desire to find a replacement father, but the story belies this claim.

Shulman’s Plato acts like a sexually obsessed stalker. He arranges to be around Steve as much as possible, flies into jealous rages when Steve speaks to anyone other than him, and fantasies about the life he wants to live with Steve. These fantasies range from envisioning them going out to dinner at fancy restaurants to taking vacations to the big city or to romantic getaways, or even running away together. “He didn’t want to be cut off from Steve, who had stood up for him, who had taken him along. […] He just couldn’t be cut off, he told Steve with everything he could put into his eyes, and the movement of his hands.” I could go on, but, really, if Shulman didn’t know what he was writing, he was in much sadder shape than I can imagine. He literally has Plato think “Steve belonged to him.”

Shulman’s stereotypical depiction of Plato was straight out of the gay panic literature of the 1950s, a time when psychiatrists believed homosexuality was a natural phase that boys briefly experienced before the development of heterosexuality through intensive social conditioning in mid-adolescence. Shulman’s novel anticipated by a few months Exposed magazine’s feature on “Geniuses Are Potential Queers,” in which Fred Bennett used a mishmash of Freudian psychobabble and stereotyping to claim that high intelligence and social isolation made boys gay by preventing them from reaching sexual maturity. “Interestingly enough, Freud, who usually knew what he was talking about, considered homosexuality a form of arrested emotional development. Maybe that’s what’s wrong with the homosexual-genius. Cut off from the rest of humanity the way he is, maybe he’s never had a chance to grow up.” This was also the theme of Shulman’s novel, plus or minus some bad parenting.

The novel’s lackluster plot, such as it is, only starts to come into focus in the back half of the novel, when Steve and Judy decide to become a couple, to Plato’s horror. A very long love scene, going on for pages, finds Judy waxing poetic about the cosmic nature of their love and Steve confessing his love for her as Shulman emphasizes traditional gender roles. “They looked at each other, and they were happy: Steve because he was in love as a man; Judy because she had always wanted to be loved and loved completely.” The parallel scene in Rebel is much less traditionally romantic. Judy starts to tell Jim she loves him and Jim replies only with, “Well, I’m glad.” And then it’s over. (Jim’s words were nearly verbatim what Dean told Liz Sheridan when she tried to get a confession of love from Dean a few years earlier.)

This love, however, is a threat to Plato, whose psychopathic tendencies flare into insanity as he seeks to win back Jim from Judy.

Plato, aware of a new and more meaningful relationship between Steve and Judy, looked to Steve for reaffirmation of their friendship. He really disliked her, the witch-bitch, for Judy held possessively onto Steve’s arm and looked at him as if he was the last thing she ever hoped to see. He was losing Steve through no fault of his own. Hadn’t Steve pulled Judy after him to the car and left him with Buzzy, who was really scorching and had started at least four or five times to crack him a couple just for release? He was losing ground and had to stop it from slipping under his feet. Never before had he felt so unhappy, so alone, so without a toe hold, so without a minimum grip on something that would make him feel better, not so left out.

Shulman’s Steve, incidentally, is not the robust heterosexual you might imagine but is instead teetering on the brink, torn between Plato and Judy, and thus in the 1950s idiom, between arrested homosexual development and full heterosexual maturity. Shulman writes that Steve is attracted to the homosocial life Plato promises but that Judy is preventing him from falling into the trap of male intimacy through her witchy power, the one that ends the carefree life of bachelors and turns them into miserable boyfriends, husbands, and fathers. “And Steve, suddenly understanding certain adult stresses, looked unhappily at Judy in the hope she would relent. But Judy’s expression was even stiffer, more fixed; she was going to have her way.”

The final act of the novel then becomes an all-out battle between Plato and Judy for control of Steve. After Plato’s psychopathic rage leads him to murder a woman, police begin investigating the group of teens. Plato brings Steve and Judy to his house to show them his large stockpile of guns and to tell them about his loneliness—a distressingly modern touch in a novel from 1956. Plato’s final attempt to seduce Steve away from Judy fails, and he snaps, taking the two hostage in his house and becoming spitting mad at Judy, but also with Steve. He tells Steve that his gun is a better friend than Steve. “‘This [gun] won’t let me down’—he looked with hatred at Judy—‘for a woman.’”

I won’t belabor the overlong, overly violent ending. After a length standoff and shootout, Steve and Judy escape the house to join their parents and the police. However, Steve has an attack of homosexuality—sorry, conscience—and feels intense sympathy for Plato. He decides that he has to try to save Plato before the police kill him. So, he hatches a plan to go talk to Plato and convince him to surrender with a promise that they can be friends and he will stand up and care for Plato. Judy sees the two boys bonding and decides she has to put a stop to it by—and I can’t believe I’m writing this—leading the police into battle against Plato to reclaim Steve: “She saw herself losing him, realized it as he stood on the path with his right hand extended to Plato in a gesture of friendship, compassion, and understanding. […] And she had a right to this boy as her mother had a tight her father. If Plato returned with Steve she was lost.” Therefore, she connives to induce Plato to take a shot at her.

Plato was rattled. He looked from Steve—his friend—to this monstrous girl who ran to separate them again, and he snapped a bullet at her and missed because his glasses were misted. A policeman who had been watching carefully and had never relinquished his aim on Plato fired and the bullet whined into Plato’s shoulder, knocking him backward against a pillar. As he stumbled for balance a second bullet hit him with the impact of a battering-ram and he tried to fire the carbine at anyone because he hated them all and was going to die ignominiously, foxed by people he held in contempt. He couldn't make his left hand do what his mind commanded and he fell against the open door, pulled the pin on the grenade to hurl it toward the lawn—and suddenly felt tired, very tired. He hated the house, which was more important to hate than the stupid people outside, fell forward on the grenade, and knew only an explosion.

Thus, as was required in the 1950s of all gay characters, Plato had to die, preferably miserably, to destroy the taint of sin.

To his credit, Shulman did not try to do what Nick Ray did and have the remaining two teens suddenly discover that the magic of heterosexual love erased all the trauma from their lives. Shulman’s Steve, unlike Ray’s Jim, is too traumatized by the violent cataclysm to immediately rejoin Judy. However, Shulman sees this as weakness and symptomatic of the failure of young men to achieve the right level of emotional deadness required of adult life. Left to contemplate his bisexuality—sorry, his masculinity—Steve laments that he could not save Plato and worries that he will not be man enough to save Judy from her witchy ways and reassert his masculine dominance in the relationship.

Children of the Dark is a very bad book on many levels, and it is a great thing that it did not make it to the screen to become another tale of an evil homosexual psychopath like The Strange One (1957, from a 1947 novel) or, in literature, The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955). It is, however, an instructive look into what might have been, and also explains some of the weird storytelling choices in the final film as the cast, the writer, and the director worked to turn a deeply unpleasant story of a psychopathic teen’s fatal attraction into a much more sympathetic and humane story. At the end of the day, the queer themes we see in the finished film are the unintentional result of Shulman’s failed effort to create an evil homosexual monster.