Stephen Kijak's Magnificent Obsession

The filmmaker's new documentary about Rock Hudson rewrites history to turn a stolid, fallible, and ultimately cowardly man into a hero of gay liberation.

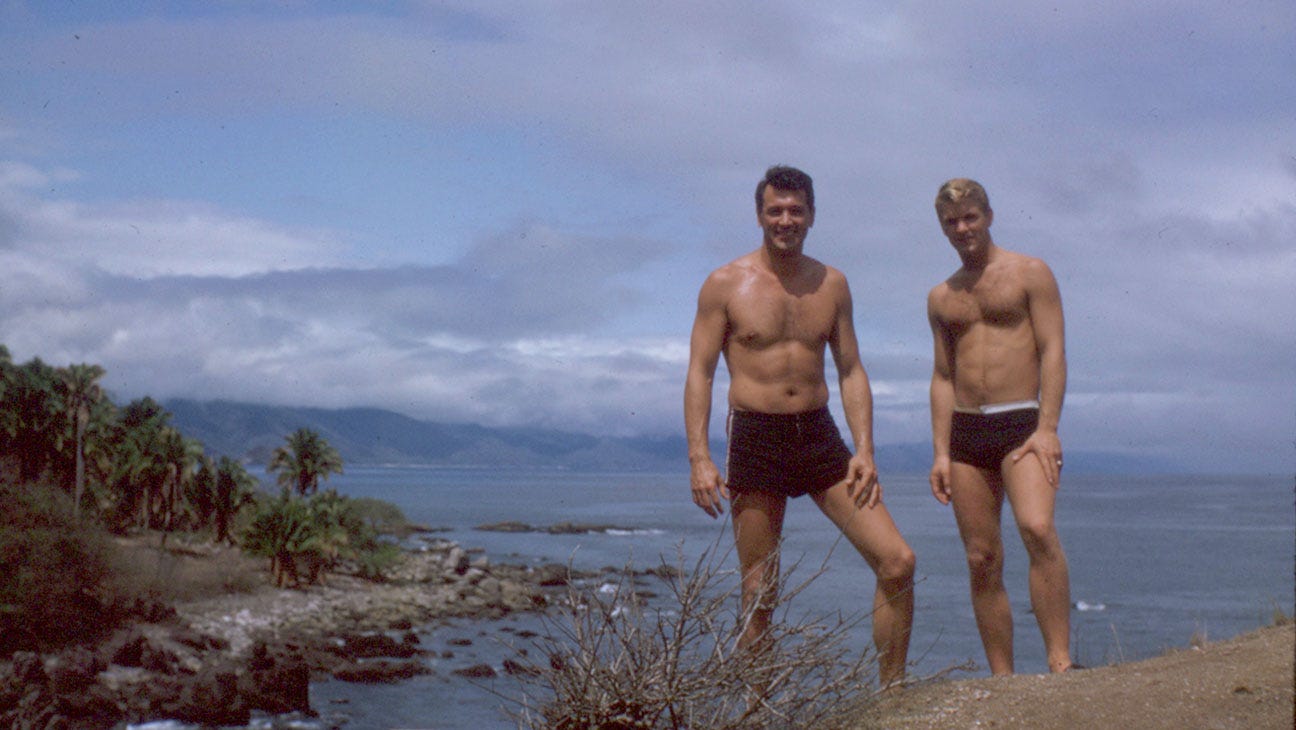

This week HBO debuted Stephen Kijak’s documentary All That Heaven Allowed, a biographical portrait of closeted movie star Rock Hudson, with a special focus on his private—and very secret—gay life. “We have to constantly keep telling these stories, creating openness around gay lives, because, as we see in Florida and many parts of our country, we’re in this vicious backslide with queer rights and violence against gay people and trans people,” Kijak told Vanity Fair. “I don’t know if we’re reclaiming, or just claiming Rock as one of our gay icons.” After watching the documentary, I thought Kijak went a little too far in trying to make Rock Hudson into a gay hero.

The outlines of Rock Hudson’s life are fairly well known. He grew up in a broken home with a stepfather who beat him to try to stop him from pursuing an effeminate and likely unlucrative life in the theater. He served in World War II and then moved to Hollywood where he fell into the orbit of the entertainment industry’s network of gay men, who taught him how to live a double life as an aggressively straight public figure and a privately gay lothario. His sexually predatory agent, Henry Willson, trained him to act butch, and despite his evident lack of acting talent—he notoriously could not remember his lines—his looks carried him from one picture to the next until he became a major star. He entered a sham marriage in 1955 that lasted three years, had the Hollywood vice squad and the FBI (along with multiple White House administrations) tracking his sex life, engaged in an almost ungodly amount of sex with countless lovers, contracted AIDS, and died without ever admitting in public to being gay.

In late 1985, as he was dying, he hired writer Sarah Davidson to tell his story in a semi-autobiography, which discussed his homosexuality, though much of what Davidson wrote was “recreated” in Hudson’s voice, from fragmentary interviews and recollections from ex-lovers. The 1986 publication, Rock Hudson: His Story, served as the primary source for Mark Griffin, whose biography All That Heaven Allows: A Biography of Rock Hudson cites the book dozens of times and in turn became the foundation for the documentary.

All That Heaven Allowed tells some of this story, but it pulls its punches to recreate Hudson as a hero of gay liberation. The choices Kijak made are, at times, baffling. He omits much of Hudson’s abusive childhood and his stepfather’s disapproval of his career path. He downplays Hudson’s trauma growing up gay and isolated in on a farm, and he omits the story told in Davidson’s book that Hudson first learned of gay sex when an older farmhand initiated him—we would label it sexual molestation or statutory rape today. Kijak wants to iron out the complications from Hudson’s life to tell a simple story of a man who discovered himself and lived with joy.

Because Kijak wants Hudson to be a hero, he also omits nearly anything negative about Hudson, no matter how innocent. We don’t hear that he hated deodorant, which he considered effeminate, for example, and friends often commented on how bad he smelled. (In the 1950s, deodorant was used mostly by women and gay men, and advertisers had only just started to market it to straight men.) Kijak paints Hudson as not just a great actor but also Hollywood’s top talent, despite his often wooden performances, inability to remember lines, and relatively uninteresting filmography. Kijak claims that women wanted to be with Hudson and men wanted to be him, but that doesn’t match the evidence available. It’s true that Hudson was quite popular among women, but there is little documentary evidence that men admired him. He does not, for example, appear on lists of favorite actors published into the late 1950s, and when he is written about, he appears in magazines with a primarily female readership. Male magazines did not cover him, for example, with anything like the ink they gave to John Wayne or James Dean. The extant evidence suggests men of the era saw Hudson as a woman’s idea of a man.

Similarly, Kijak heavily downplays Hudson’s promiscuity. He was a frequent presence at gay clubs and, especially, at private orgies. We see a Hollywood vice squad report about one such orgy flash by on screen, but in order to paint Hudson as a noble figure, his bed-hopping is reframed not as a pathological inability to give himself over to serious relationships but rather as an expression of joy. How much different would his several close calls and near-exposures have appeared in the documentary had it discussed that one millionaire who hosted such orgies rigged the house with hidden cameras and photographed the men en flagrante and kept files on them? The FBI received copies when Hollywood Vice seized them following a raid. It also would have been worth interrogating Hudson’s use of sex workers, including men provided to him by his good friend, the famous L.A. hustler/pimp Scotty Bowers, and the exploitation of vulnerable young men, particularly teenagers and unemployed ex-military men, to fuel the orgies and house parties men like Hudson attended and hosted.

Instead, Kijak gives us Hudson biographer Mark Griffin admonishing James Dean for reacting poorly to Hudson sexually harassing him on the set of Has Anybody Seen My Gal in 1951—an anecdote Kijak edits to wrongly imply it happened on the set of Giant in 1955. (Griffin knows better; he got it right in his book.) They’re men, after all—they’re supposed to like sex. Griffin can be heard attributing the story to “the rumor mill,” though in his book he correctly identifies it as a passage from William Bast’s 2006 memoir Surviving James Dean, and Griffin adds that Dean and Hudson weren’t all that different since it is “fairly well documented” that Dean was “kept” by a “radio executive” when he was young(er). I can attest it is well-documented; I am the owner of the document, a settlement agreement outlining the money Rogers Brackett spent on Dean during their two-year relationship and ending his lawsuit against Dean demanding that Dean pay it back.

Nevertheless, I think both Griffin and Kijak make a bit of a mistake by assuming that every closeted man of the 1950s was equally as hypocritical as Hudson and benefited as much from the gay culture of the era. Hudson and Dean do indeed have striking similarities—their midwestern backgrounds, complicated family life, discomfort with being perceived as gay, and struggles to enter the world of acting. But the two men experienced their sexuality in very different ways. By chance, when he arrived in L.A., Hudson fell into a more-or-less supportive environment with a series of friends and lovers who were more-or-less his equals and integrated him into a sub rosa world that offered freedom behind closed doors and protection in public. By contrast, Dean struggled much more. He struggled internally with his sexuality and wondered whether he could become straight. He also experienced repeated sexual abuse and exploitation from men who claimed to love and support him, who never considered him an equal. While Rock Hudson looked the part of a hulking straight stud, no matter how much Dean performed the rituals of masculinity, his boyish appearance got him labeled “androgynous” and even “effeminate.” In short, Hudson’s experience was that of a small minority of well-connected urban elite gay men, while James Dean’s experience, until his last year or so, was closer to that of the countless queer men who were not part of the small, urban gay culture. (Bast’s memoir even contains a few passages discussing why Dean, who refused to be effeminate even in private, did not fit in with the performatively campy gay networks of New York and Hollywood and was thus excluded from them.)

By the end of All That Heaven Allowed, Kijak lionizes a dying Rock Hudson for closing his mouth while kissing Linda Evans on the set of Dynasty, “protecting” her from his AIDS, which experts at the time feared could be transmitted by kissing. It was hardly an act of heroism to put someone at risk to protect your own secret, and contemporary notes from a Hudson associate quoted in the film even worried that Hudson had just infected her and if it were unethical to keep hiding his AIDS diagnosis. But Kijak throws that concern overboard to pretend that Hudson dealt nobly with his disease. It’s all a bit much. In trying to make Hudson into a hero and gay icon, Kijak overlooks too many details. A stronger approach might have examined how Rock Hudson’s story reflected the types of lives queer men of that era lived so that we could see that every man who survived in those times had some degree of heroism and that living was itself a noble act worthy of celebrating without the theatrics, fanfare, and rewriting necessary to turn real people into gilded saints.

"A stronger approach might have examined how Rock Hudson’s story reflected the types of lives queer men of that era lived so that we could see that every man who survived in those times had some degree of heroism and that living was itself a noble act worthy of celebrating without the theatrics, fanfare, and rewriting necessary to turn real people into gilded saints" I wanted to quote this section in whole because it says it perfectly and I couldn't say it any better. I haven't seen the documentary myself, but it feels like that by glossing over aspect of Hudson's life/career and trying to turn him into a beyond reproach hero/icon it did a real disservice to everyone and Hudson's experiences and life story/the larger history.

You hit on something that I was (not as articulately or precisely) thinking about myself: "In short, Hudson’s experience was that of a small minority of well-connected urban elite gay men, while James Dean’s experience, until his last year or so, was closer to that of the countless queer men who were not part of the small, urban gay culture." And it feels like that sort of double standard /not extending the same empathy/understanding/sympathy to Dean as they do for Hudson for both mens' experiences of being queer men in Hollywood in the 1950s is also carried through in this documentary itself, which is frustrating and unfortunate.

Terrific piece, Jason!