"The Best Possible Denial"

Vogue magazine's new piece on James Dean's relationship with Pier Angeli tries too hard to rescue Dean from homosexuality.

This week, various editions of Vogue magazine published a lengthy piece on the failed romance of James Dean and Pier Angeli, born Anna Maria Pierangeli. The original Italian article by journalist Giacomo Aricò, published on Wednesday, and the truncated English adaptation published on Friday contain a number of misrepresentations and errors that came from the telephone game of repetition and PR that passes for “celebrity” coverage in our media. But the broader purpose of the piece, as the author writes in Italian, is to deny that Dean was either homosexual or bisexual, a remarkable claim for a major magazine in 2024. Let’s take a look at some of the ways the Vogue pieces went wrong.

The two pieces, while similar in content, are rather different in writing and even begin with wholly different paragraphs. I will try to cover the major claims made in both as well as the significant differences between the two versions. I’m sure that Aricò was not involved in translating his story any more than I was involved in translating my Esquire piece on Dean for international editions, but as he is the credited author, I will refer to him as the author when describing each article.

In the Italian edition, Aricò opens with a false claim and an unsupportable conclusion. He asserts that Dean and Angeli had a six-month relationship that culminated in a marriage proposal and that the failure of that proposal led Dean into a self-destructive death spiral. This is not factual. Their relationship lasted somewhere around two months to three months (give or take a week or two), and the marriage proposal—one of four Dean made to various women in his lifetime—did not seem to affect him much after a few weeks. The conclusion Aricò draws is suspiciously similar to the plot of the 1997 Casper Van Dien movie James Dean: Race with Destiny.

The claims appear later in the English translation, which seems to recognize that the conclusion is somewhat less that well supported.

Aricò asserts that Dean and Angeli had a “secret” relationship from May 1954 to November 1954, and that they broke up in November, after he proposed marriage. She then married Vic Damone only “days” later in a “surprise” shotgun wedding. The two versions in Vogue differ greatly but are both wrong:

Italian (my translation)

At the end of that same month [November] Anna Maria will surprisingly marry the singer Vic Damone, who was both Italian-American and Catholic, and therefore received his mother-in-law’s approval. James Dean was devastated and began to fall into an abyss of alcohol and drugs. Increasingly peevish and neurotic, he began to live frantically, as if he sensed that he had little time left. He entered a depressive state which led him to drink heavily and race motorcycles and cars: hence the prelude to his tragic end.

English

By the end of that month, she would surprise everyone by marrying the singer Vic Damone—an Italian-American and a Catholic. Needless to say, Dean was devastated. He would have other short affairs, including one with Ursula Andress. But on September 30, 1955, seven months after his break-up with Pierangeli, Dean died in Cholame, California, from injuries sustained during an accident involving his Porsche 550 Spyder. He was 24. According to legend, in the glove compartment of his wrecked car was a new letter in which he yet again asked Pierangeli to marry him.

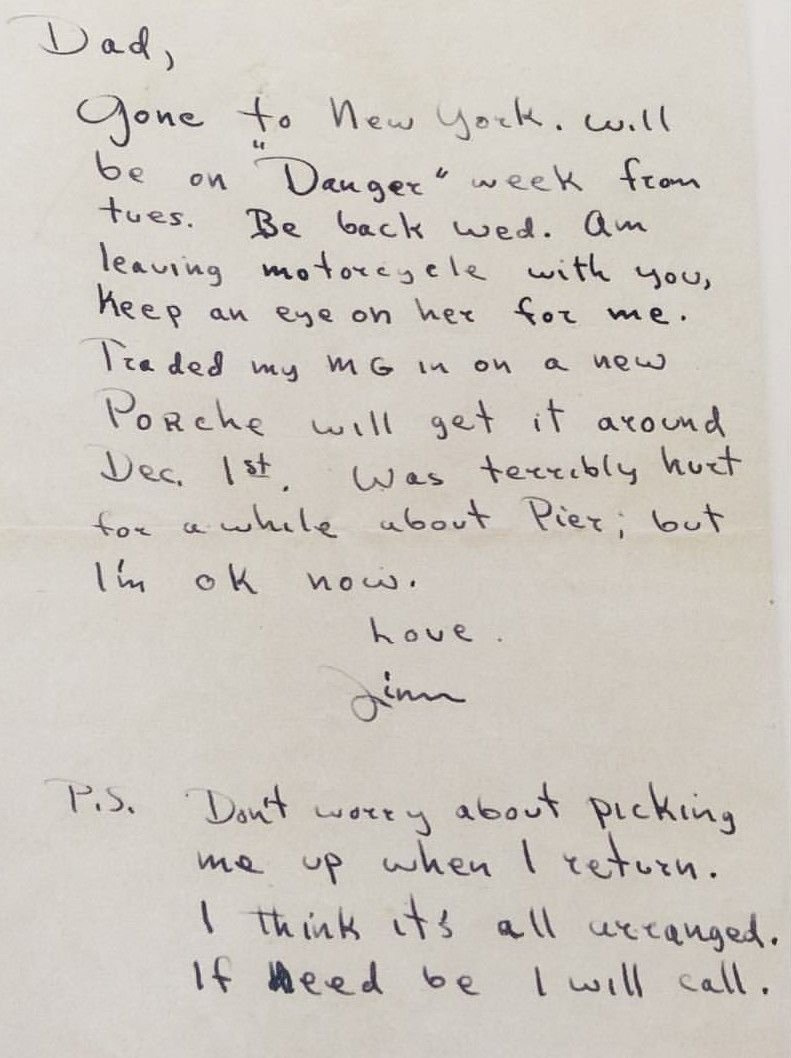

We know this is untrue for several reasons. First, James Dean himself wrote a letter to his father informing him of the breakup with Angeli and telling him that he was sad about it for a while but had gotten over it. He wrote that letter approximately ten days before he appeared on Danger, a CBS TV anthology, as he discusses his upcoming appearance. That show aired on Sept. 2, 1954, which places his letter in late August 1954. That means that their breakup occurred in mid-August 1954.

This is confirmed by a letter in my possession—the only contemporary document to mention the marriage proposal—in which Dean’s agent answers legal questions about his plan to marry Angeli. (He wondered if doing so would void his draft exemption for homosexuality.) It is dated August 12, 1954. After receiving that response, Dean and Angeli broke up and he was sad about it for—checks notes—about a week. That seems about right for a relationship of three months. Dean’s best friend William Bast similarly reported in his memoir that Dean acted sadder in public than he felt in private in order to generate sympathy in the press.

There was no letter to Angeli in the glove compartment of Dean’s Porsche, nor was Dean drinking particularly heavily in fall 1954. Indeed, he had committed that previous spring to reducing his alcohol and cigarette consumption, according to a letter he sent his agent. While this effort was not wholly successful, memoirs from friends emphasize that he was a light drinker and very rarely drunk. (His only period of heavy alcohol use occurred in 1953, around the time he struggled with what we would classify today as sexual assaults he suffered.) He did order his first Porsche shortly after breaking up with Angeli, but that was more of a function of money than the breakup; his letters state that he had planned to get a sportscar from the time he arrived in Hollywood, before he met Angeli.

Aricò’s “secret relationship” claim probably derives from Joe Hyams’s assertion in his 1992 biography James Dean: Little Boy Lost that Dean and Angeli occasionally met up in fall 1954 until she announced her marriage. This was part of Dean’s pattern of remaining in contact with women he had previously dated, a pattern that continued until his death.

We can also dispense with Aricò’s claim that Dean’s relationship with Angeli was the longest and most serious of his life. His relationships with his college girlfriend and with Liz Sheridan were both longer and more sustained. His two longest relationships were with Rogers Brackett and Barbara Glenn, though both were on-again, off-again. His relationship with Sheridan, which included a marriage proposal, was probably the most serious in terms of coming closest to marriage.

Both versions of the article grant far too much weight to the troubled Angeli’s fantasies in the years leading up to her fatal drug overdose. In 1968, she accepted payment from the National Enquirer to talk about her relationship with James Dean. By this point, after two rocky marriages, she had come to remember her two months with Dean as the happiest of her life—despite contemporary evidence, undisputed, that the pair had spent most of that time fighting. She cast their relationship as a perfect, romantic love. In 1971, she wrote to a friend that “My love died at the wheel of a Porsche.”

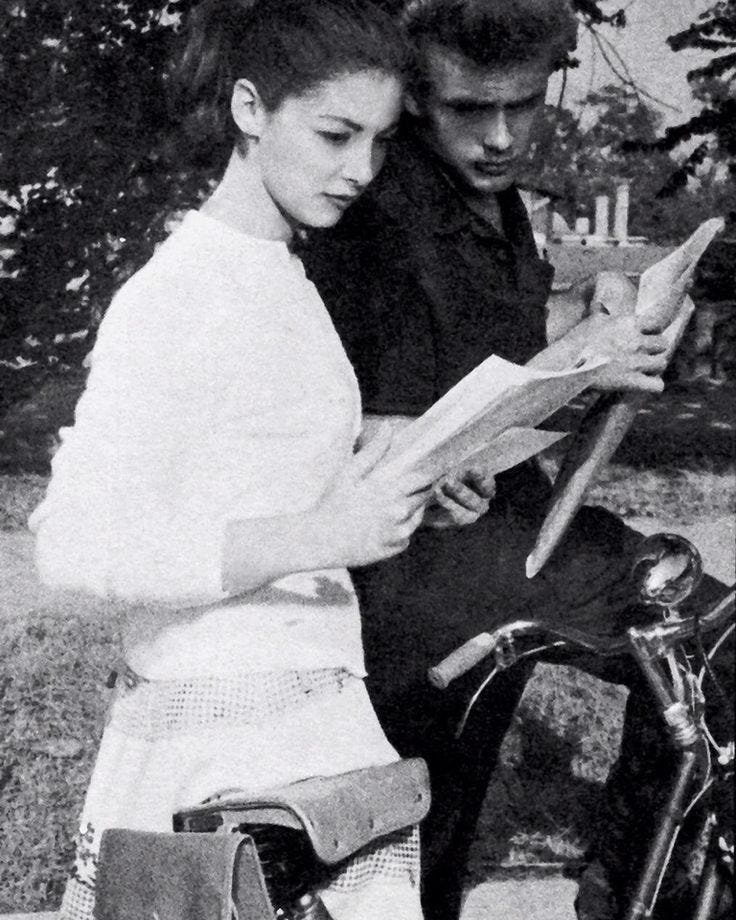

But it is also terribly obvious that Angeli was fantasizing to escape her unpleasant reality. In 1954, she was equally clear that she did not love Dean, did not want to marry him, and that their dalliance was only a diversion. While Warner Bros. pushed articles about their love on the press, complete with swoon-worthy photos of the couple, Angeli told Modern Screen—surprising because it was a fan magazine larded with studio-written puff pieces—the opposite. When asked if she and Dean were planning marriage, she said they had barely dated: “You cannot meet the first guy and fall in love right away and there you are. No, it is the wrong bit. […] I must grow up first before I fall in love.”

Similarly, Bast recalled Dean telling him that the two were not having sex and their relationship was primarily for publicity. (Elia Kazan remembered hearing the pair having loud sex in Dean’s dressing room, but Bast disputed the claim on the grounds that the dressing room was too far away and the walls to thick for Kazan to hear them.) Dean’s Hollywood agent, Dick Clayton, admitted that he had set them up as part of a publicity campaign, and contemporary letters show that Clayton did indeed organize girlfriends for Dean to be seen with, to deal with what he described in May 1954 as Dean’s “problems.” Although not spelled out, the clear implication was that the “problem,” as it was with Clayton’s close friend Tab Hunter, was homosexuality. Clayton provided many of the same women to both Dean and Hunter, and the women dutifully told the press about both men’s romantic prowess.

Aricò writes in Italian that his purpose in writing this piece was to rebut stories of Dean’s homosexuality: “Jimmy never reacted to such poisoned rumors and the love he felt for Anna Maria seems to be the best possible denial.”

Some of the other material in the articles can be dispensed with more quickly. Dean wasn’t an “atheist” as Aricò writes. He had been born a Quaker and finished his life studying Eastern religions and philosophy. He believed unwaveringly in an immaterial plane beyond the physical world, but his faith in the Christian God faded over time, in large measure because, as he told John Gilmore, he could not accept Yahweh’s punitive version of morality. We might better describe him as “spiritual” rather than religious, but not really atheist.

Aricò also accepts the 2011 claim that journalist Kevin Sessums made that Elizabeth Taylor had told him in 1997 that Dean was “haunted” by sexual abuse he suffered at the hands of his minister at the age of 11. This is a bit too complex to get into here, particularly the historiography of the molestation claim, but Sessums “improved” the quotation he published after Taylor’s death, adding in many details she never said. I obtained the audio recording of their interview, and this is verbatim what Taylor actually said: “I loved Jimmy. We used to sit up and … Off the record? He was eleven when his mother died. He was molested by his minister.” Sessums revised this into something she didn’t say: “When Jimmy was 11 and his mother passed away, he began to be molested by his minister. I think that haunted him the rest of his life.”

Vogue is part of the Condé Nast empire, sister publication to The New Yorker and Vanity Fair. I am surprised to see them publishing such a flawed piece that rehashes an epic love story originally invented by studio publicists to counter rumors about Dean’s sexuality.

Hello,

I wanted to know if is it true that before her death, Anna Maria Pierangeli wrote an unaddressed letter to her "great love" ? and if this letter is made public.

source: vogue

thanks in advance,