The God That Wasn't

A review of a new anthropological study of the people who worship James Dean.

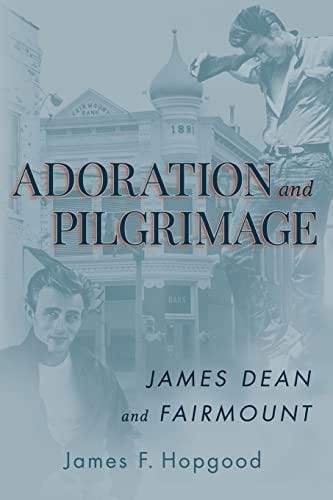

Adoration and Pilgrimage: James Dean and Fairmount

James F. Hopgood | Luminare Press | 2022 | 282 pages | 979-8886790108 | $18.95

The current issue of Mojo, a music magazine, features an illustration of James Dean driving toward the reader in the Porsche Spyder in which he died. The singer Weyes Blood sits beside him as he speeds away from a flying saucer, its tractor beam chasing them toward Dean’s inevitable death. The striking image illustrates a line from Blood’s new song “Grapevine,” but the unusual portrait also suggests a longing to follow Dean into death, as though his demise were an act of transcendence, an event of cosmic importance. It’s not the kind of image you find associated with most celebrities. You don’t see much fan art of political junkies depicting themselves riding through Dealey Plaza alongside JFK, nor are there many beatific images of Marilyn Monroe as a psychopomp guiding fans to heaven.

And yet, as anthropologist James F. Hopgood explores in his new book Adoration and Pilgrimage: James Dean and Fairmount, such imagery is common among James Dean fans. In what he describes as the first ethnographic study of its kind to be performed within the framework of anthropology rather than media studies, Hopgood seeks to understand why Dean fans seem uniquely dedicated to their idol and whether their devotion to a long-dead movie star constitutes a religious cult. He has spent more than three decades looking for the answer, and the resulting book is something of a shrug, an incomplete, sometimes insightful and often frustrating exploration of the line between fandom and religious worship.

Adoration is the culmination of field research Hopgood began in 1989 and the last in a series of academic papers the now-retired professor has published on Dean fans. It is also a self-published work, longer than an academic journal article, but somewhat short for a book (page count notwithstanding). Let us dispense with the technicalities. As a self-published effort, it is in desperate need of editing. Sentences and sentiments repeat frequently, often to the reader’s annoyance. Structured like a dissertation rather than a narrative, the book lacks a sense of drama or momentum, and in places the author contradicts himself, seemingly without noticing he has made mutually exclusive statements. It also offers little by way of conclusion, and many of the author’s observations seem rather sweeping as generalizations since they rest on a couple of dozen interviews of varying depth (I don’t believe Hopgood gives the exact number) and a reading of a James Dean fan club’s newsletter archive.

If Jupiter is sometimes described as a failed star, the posthumous image of James Dean (amalgamated from his movie characters and a highly redacted selections of the real man’s biography) might be a considered a failed god, a sort of Apollonius of Tyanna, who for lack of an organized church and a driven, proselytizing apostle to lead it never quite crossed the boundary of divinity, despite a group of his admirers attributing to him the qualities of one.

In Adoration, Hopgood seeks to explain the behavior of a subset of Dean fans, those that treat him more or less as a divinity, the kind of people Warren Beath profiled in The Death of James Dean (1986). Both Beath and Hopgood appear to be (or to have become) fans of James Dean, but where Beath plunged headlong into the world of Dean adoration, Hopgood attempts to maintain an academic distance from his subject, albeit with limited success. Perhaps this is why Beath’s book is barely mentioned in Hopgood’s, noted only in passing as a book Dean fans sometimes read. In imposing an academic framework, Hopgood divides Dean fans into three categories (a) casual fans, who have only a mild interest in Dean or his movies; (b) serious fans, who have a strong interest in Dean and may collect memorabilia but this does not play a major role in their lives; and (c) extreme fans, whom he calls the “Deaners.” Their propensity to organize their lives around Dean, make pilgrimages to sites associated with Dean, and seek philosophical or spiritual guidance through ritualized communion with Dean marks them as categorically different from even serious fans, in Hopgood’s estimation. Hopgood estimates the total number of such fans at around 3,000 worldwide, though he has no statistical basis for the figure other than James Dean Remembered newsletter subscription figures and the questionable notion than such fans by necessity must visit Fairmount, whose spotty tourism statistics serve as gauge. I would dispute those assumptions and suggest that many who would otherwise fall into Hopgood’s “Deaner” category likely engage with Dean privately, without outward public performance of ritual. Even Hopgood’s own “Deaners” often admit to keeping their passion hidden from family and friends most of the time.

Here I must stop to note that Hopgood does not prove a categorical difference between types of fans, since he did not study the first two groups of fans and their behavior, nor did he prove the processes he studied unique to Dean, for he did not examine extreme fans of other iconic celebrities. Indeed, he writes of his own lack of awareness of pop culture research and the lack of rigorous academic studies of popular culture figures in the literature. I would wager that a good number of those who idolize Princess Diana or declare Donald Trump God’s mortal instrument, for example, engage in similar cognitive behaviors, as do the super-fans reading Taylor Swift’s lyrics for hidden messages, and it is more than likely that a larger number of Dean fans perform private remembrances and acts of identification and communion than the number who make pilgrimages annually to Dean’s childhood hometown of Fairmount, Indiana to attend various events. The formulation “What would Jesus do?” has been jokingly applied to many celebrities, but undoubtedly there are those who do indeed consider how role models think and behave before making decisions, just as those who hold James Dean in that role told Hopgood they do. We might even compare Deaners and Trumpists in their counterfactual citations of their love-object’s “honesty” as justification for their love, despite ample documentation of wild lying.

Hopgood also takes the unusual step of excluding from his study those who allege supernatural contact with Dean’s soul, claiming he finds the subject distasteful. Nevertheless, supernatural elements make their way in, as they would in any study of religion, and the occasional psychic contact, sign from above, or message from beyond finds its way into seemingly rational fans’ lives.

That disclaimer aside, Hopgood’s description of the “Deaner” behavior certainly implies a different level of devotion than many other celebrities receive. Hopgood focuses the majority of his analysis on individual behavior, primarily on the way his informants develop an imagined relationship with Dean through the performance of personal rituals, the consumption of Dean-themed media (both Dean’s own and that of others), and the use of photographs and memorabilia as icons that facilitate a direct connection to the charismatic figure whose guidance and support they seek. The scale of Dean fandom is also a subject of interest. Undigested sections of the book not directly relevant to the putative religious topic describe the rivalry between the Fairmount Historical Museum and the James Dean Gallery (which I will discuss below), the trademark battle over a Dean-themed car race, famous singers’ use of Dean in their lyrics, and other aspects of Dean-as-image that, strictly speaking, are artistic or financial and not acts of religious devotion. I sincerely doubt Taylor Swift had cult thoughts in mind when referencing Dean as a style icon in her song “Style.”

The book is structured around interviews with a small group on Dean devotees who have elected to take up residence in Fairmount or make regular and sustained trips there. Hopgood describes true believers who maintain shrines in their homes, light candles and make offerings to Dean, travel with his portrait or biography at all times, make annual pilgrimages to sites where Dean spent time, and engage in acts designed to integrate themselves with him. These acts take various forms but can involve producing pieces of art or poetry to glorify him, seeking guidance in life decisions by imagining how Dean would act, and, in the most extreme cases, moving to Fairmount to surround themselves with him both physically (in terms of location) and socially (in terms of a Dean-focused community). The final stage of commitment to Dean seems to be a regular or permanent residence in Fairmount, near to his grave.

At the annual memorial service held at the Back Creek Friends Church each September 30 to commemorate the day of Dean’s death, the proceedings mirror a Christian Good Friday or Easter vigil. And like the original Christian liturgical calendar, the commemoration of Dean’s passion and death far outstrips the celebration of his nativity in both scale and sanctity. On September 30, Dean’s face is projected behind the pulpit, equal to the painting of Jesus beside him. The service follows the form of a Protestant eucharist, and—in a detail that shocked even me—pages from David Dalton’s 1974 James Dean biography The Mutant King are read aloud where Bible passages appear in a standard service. “Deaners” call Dalton’s book (out of all the Dean biographies) “the bible,” perhaps more because of its supernatural coloring than in spite of it. Dalton is the only biographer to present Dean in divine terms, as an all but literal reincarnation of Osiris and avatar of American mythology. Following the service, worshipers walk in a procession to Dean’s grave to sing hymns to the dead hero. Hopgood recorded the faithful reciting a liturgy drawn from the worship of Christ: “Dean will live forever. Dean is king. He is the true son of God. He is eternal.” Hopgood declines to point out the substitution of Dean for Jesus.

Hopgood’s analysis is marked with several strange elisions that an outside observer might attribute to a growing attachment to the Dean cult. Decades ago, Hopgood first believed that the Dean worshipers were a cult, who held Dean as their fetish, performing a kind of religious worship. But, over time he has come to find the traditional anthropological terminology inappropriate because the pejorative use of “cult” and the sexual use of “fetish” in popular media could be insulting to Dean fans. Consequently, he chooses not to categorize Dean adoration as a cult or veneration of his memorabilia as fetishism despite the evidence.

Similarly, he appears overly deferential to the remaining members of Dean’s family, particularly Dean’s cousin Marcus Winslow, Jr., who controls Dean’s image, profits from merchandising, and has very strong opinions about what should—and should not—be said about James Dean. Dean left Fairmount when Winslow was five, and Winslow saw him only twice more before Dean died when Winslow was eleven. Nevertheless, Winslow vehemently insists that he knows Dean was robustly heterosexual and has used his control of the Dean estate since its incorporation in 1984 and a landmark power-grabbing lawsuit against Warner Bros. in the 1990s to suppress discussion of Dean’s sexuality in mainstream media—which is why it has been treated sparingly since the middle 1970s. The 1974-1976 flurry of media depicting Dean’s likely queer (bisexual, homosexual, etc.) sexuality, including a surprisingly frank NBC-TV movie, caused great “pain” to Winslow, according to Hopgood, and any modern project seeking access to images of Dean or cooperation from his estate (and, by extension, that of any other celebrity in the extensive portfolio of the management company, Curtis Management Group, built atop Dean’s foundations) effectively cannot openly discuss his sexuality. Indeed, when Paul Alexander wrote Boulevard of Broken Dreams (1994), a Dean biography, he hid his thesis that Dean was gay from CMG, Winslow, and the Fairmount Historical Museum (which houses much of Winslow’s Dean archive) to secure their cooperation. Hopgood reports that the guardians of Dean’s image still refer to this action as a “betrayal,” and unsurprisingly, major media like the New York Times trashed the book.

In courting Winslow’s favor, Hopgood has chosen to ignore one of his own most important findings. He treads delicately around the issue of Dean’s sexuality, acknowledging the existence of differing views but, in a strange argument, suggesting that James Dean is unknowable and the stories told of him are unreliable and therefore can be discounted. (So, what, exactly, does he think he collected in his ethnographic interviews, which were, of course, also unconfirmed stories?) This leads to strained passages where Hopgood tries to describe the rivalry between the Museum and Gallery and their very different approaches to Dean. The Museum depicts Dean as wholesome, heterosexual Americana, while the Gallery, run by a married gay couple, is more heterodox and leaves space for queer readings of Dean. Hopgood acknowledges grudgingly that homophobia played a role in local opposition to the Gallery in its first decades, but he frames the rivalry (which at times included active Museum and civic efforts to drive visitors away from the Gallery) in terms of “Big City,” “liberal,” and “outsider” elements impinging on a traditional space. Those words are obvious code for “gay,” since no one cares about straight, Republican outsiders. This is all the stranger since Dean was himself much franker about this than Hopgood. Inside the cover of his copy of a biography of a gay Spanish playwright, Dean composed a poem about Fairmount: “My town thrives on dangerous bigotry,” he wrote. “My town is not what I am, I am here.”

In his own autobiography last year, Gallery owner David Loehr said that the Fairmount homophobia of the 1990s has largely dissipated at an interpersonal level, and Fairmount is now much more welcoming to LGBTQ+ people. But it is obvious that a different standard applies to Dean. The older residents of Fairmount who knew Dean in youth insisted he could not be queer because he hadn’t been that way when he lived there as a teenager—a laughable syllogism to any closeted twentieth century teen—and even today, there remains discomfort with the idea that someone who could arguably be described as the iconic embodiment of young American manhood might not have been 100 percent straight. It is unthinkable because it would undermine the fantasy of America and the self-image of so many, especially men, if the idealized American male was queer. It’s one thing to tolerate queer folk as an exotic other, but something else to idealize one.

Hopgood, deferential to Fairmount’s self-image, shies away from drawing any conclusions about homophobia or queerness, a massive blind spot made obvious when his informants all but beg him to talk about it.

All of the informants—without exception—report developing their infatuation with James Dean during adolescence, a fact Hopgood chooses not to notice because he prefers to categorize Dean fans—and here he conflates “Deaners” with “serious fans”—by race and religion, identifying them as overwhelmingly Anglo-American Protestants, with an “occasional” Italian or Jew. (Hi! Being half Austro-Polish, I am only occasionally Italian, mostly at the occasion of dinner!) And he also omits another key element: Most, though certainly not all, of the hard-core Deaners he met are men, and the majority of them are queer. One after the next speaks of his husband, male partner, or boyfriend, and many heavily imply that Dean’s example served to guide them through difficulties coming to terms with their sexuality, particularly in the more homophobic twentieth century. A professor of philosophy speaks guardedly of his sexuality and expansively of Dean revealing hidden levels of reality to him. This is very similar to previously published accounts from men of the 1970s. For Hopgood to ignore this obvious data point must be a purposeful choice, particularly when he talks of Dean fans’ sexual desire for their handsome hero while glossing over the disproportionately high number of men in that number. He seems uncomfortable at the suggestion that artist Kenneth Kendall’s infatuation with Dean’s “angelic” beauty was not merely religious ecstasy.

So, overall, Adoration and Pilgrimage is an interesting but incomplete study, one that offers insight into the process and function of celebrity adoration without quite following the lines of evidence to their ultimate endpoint. It’s useful more for the information it provides than the conclusions it circles around. However, the value of a study of Dean-as-religion will continue to have ongoing value. As I wrote this review, the famed songwriter Jack Tempchin released the first music video generated by artificial intelligence machine learning, for his song “Ghost Car.” The subject? James Dean as a supernatural psychopomp and cosmic intercessor, carrying Tempchin’s soul through the veil of the cosmos.

Glad to see this extended review. Shame with so many pop culture sociological studies of great depth written now we only get this timid, somewhat waffling and rambling narrative that comes to no real conclusions.

Dean certainly falls into the basket of the Young & the Beautiful cut down in the flower of youth yet becoming legendary if not immortal (Adonis, Attis, Narcissus, Antinous, etc.)

And, yes, knowing Kenny Kendall and having briefly had his bust of Steve Reeves pass through my hands, he was infatuated with both for reasons quite distinct from spirituality.

As to the song and image referenced at the start, it reminded me immediately of the nearly contemporaneous Betty & Barney Hill incident.

In interests of full disclosure, I have a poster of Dean in my front foyer that greets every guest. But only because it was the last spot on my walls not already covered by bookshelves or artworks. But I suppose that makes me a 'Deaner' as well.