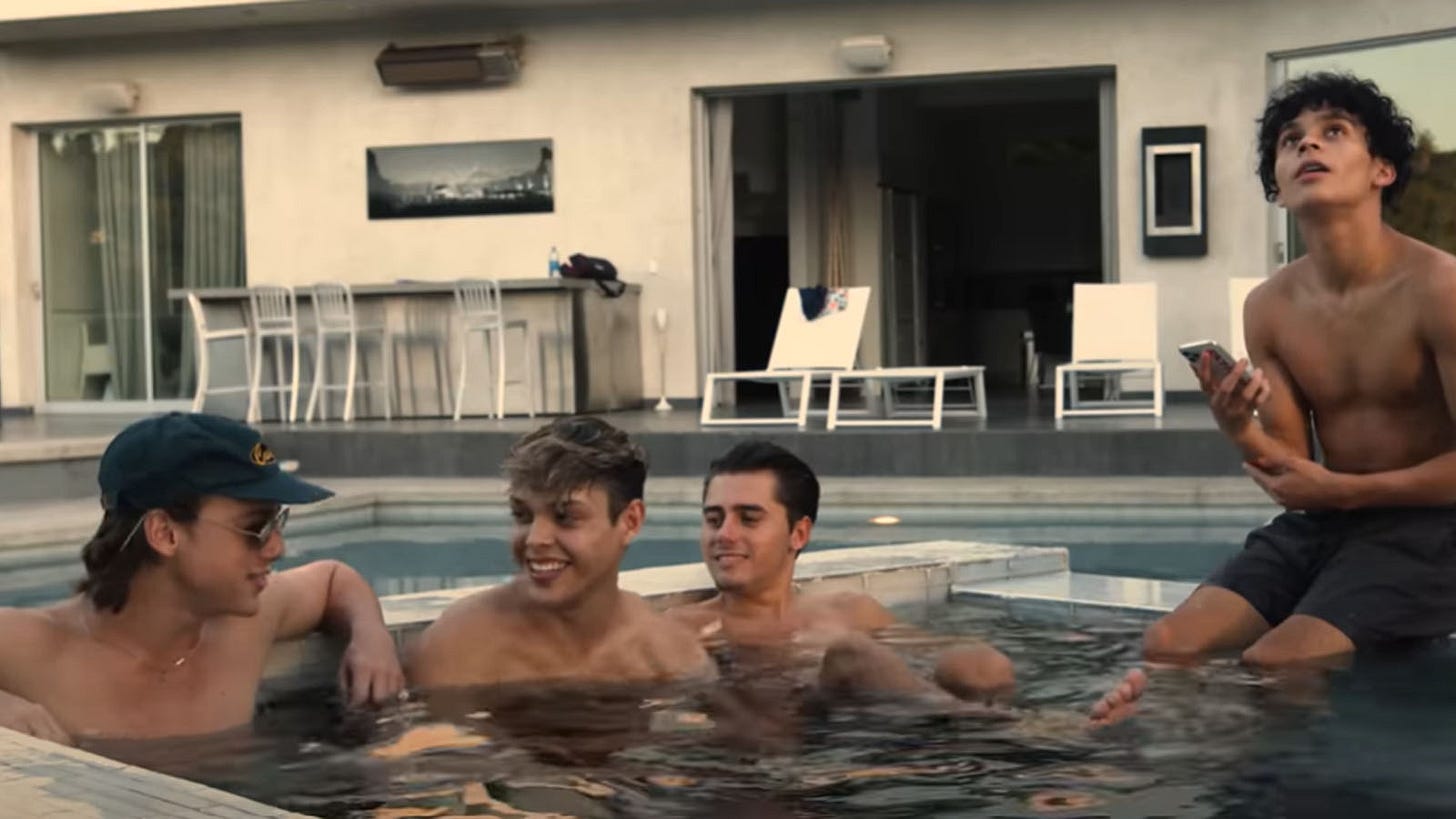

“Yo, bro, bro! I was just kidding!”

The "angry young man" was a literary staple of the 20th century. But today it's middle-aged men who are angry at youths for not being angry.

A few days ago, Jacques Vallée and Paola Harris released their much-hyped new book, Trinity: The Best-Kept Secret, the one that Chris Mellon and Brandon Fugal and a squad of UFO celebrities promised would bring the goods and change ufology forever. That didn’t happen. The thinly sourced book offered meandering anecdotes from two old men who claimed to have seen a crashed avocado-shaped spaceship as children in 1945 and their nearly as ancient cousin who claimed to have played with the wreckage that the pair kept around the house. The much-hyped tests of supposed wreckage provided no real results, and Vallée speculated, ludicrously, that UFOs aren’t extraterrestrial but instead are “gifts” or “warnings” from a non-human intelligence that manifests as a universal consciousness, purposely sent and crashed on backwater farms to help us level up in some bizarre cosmic game.

And that was only the second stupidest thing a member of the UFO club did this week. Lue Elizondo, fresh off his appearances on ABC’s This Week and CNN’s The Lead warning of the dire national security implications of the UFO threat, decamped to Josh Gates’s paranormal monster-hunting show Expedition X on the Discovery Channel to try to track underwater space aliens. Because he’s super-serious about national security. This is the guy Congress is listening to.

Since I can’t deal with any more of the media’s inability to think critically about UFOs—seriously, George Stephanopoulos and Jake Tapper, not a single challenge to Elizondo’s assertions between you?—I instead want to talk about a new piece in Harper’s magazine this week from writer and English professor Barrett Swanson profiling a group of adolescent boys who made TikTok videos from the Los Angeles mansion they shared, raking in what they called an “absurd” amount of money from sponsors. Their management company, which has since closed their house as unprofitable, took 20% of their earnings in exchange for room, board, and promotional platforms.

Swanson’s prose is impeccable, his tone of mournful regret a master class in creating meaning out of emotion disguised as dispassion. Although Swanson must be younger than me—I’m forty, while Swanson wears a hipster beanie and describes himself as a Millennial—he seems entirely disconnected from youth, almost resentful of not just kids these days but the very notion of being young and beautiful and free. His article brims with the casual resentment of a lonely middle-aged man for the easy intimacies of youth, bristling at the notion of friendship and fun, longing for others to adopt the posture of unpleasant seriousness that he conflates with maturity. (He describes himself as suffering from depression.) He laments that social media pays better than his chosen profession, but that is not the fault of social media or the young people making content.

His early description of the young men of Clubhouse for the Boys—the L.A. TikTok “collab house” he visited—sums up his disdain for youth, his pretentious pose of superiority, and his professional insecurities:

Now, on the pool deck, the boys tussle and roughhouse with the zeal of Labrador puppies, slugging each other lovingly in the shoulders and then retreating with giggles like ninnies. As one boy gets chased, he shrieks, “Yo, bro, bro! I was just kidding!” They’re so caught up in their own antics that they hardly even notice my presence. In this way, I can float among them like a ghost in a Henry James novel, loitering on the edge of the patio as they arrange a post for Instagram. In some sense, they are like college boys anywhere, except that they live in a seven-thousand-square-foot mansion, a residence whose value is roughly $8 million and whose rent is $35,000 a month—which, it must be said, is more than half of what I make in a year as a tenure-track university professor.

Swanson is very concerned that the boys—most within two years of twenty—lack the critical thinking skills and world-weariness that he aims to teach in his English classes, though he concedes that his students rarely achieve the self-actualization he intends for them. The young men come across, in Swanson’s telling, as vapid, overeager, too engrossed in social media and youth culture, consumed by the endless pursuit of fun and content. In the most disturbing anecdote, the boys’ media liaison, Chase Zwernemann, only 21, describes his fears of Satanism in the entertainment industry because of “symbols” he saw in Hollywood offices that a QAnon YouTube video taught him to fear. He had no idea what QAnon was but knew it had to be real or else some unknown force wouldn’t keep deleting the documentary from video-sharing sites. But this is an anomaly; the actual TikTokers seem sweet, friendly, open, and even a little naïve—just like boys their age in college.

I completely understand being despondent that teens are chasing social media fame rather than learning things, and that high-earning influencers seem somewhat vapid. That young adults buy into QAnon conspiracies because they trust social media content is terminally depressing.

But Swanson sees TikTok collab houses as a sign of the apocalypse. I have a hard time seeing young people making wholesome (if vapid) content that monetizes friendship and fun as inherently worse that the old star ladder of turning tricks for dirty old men for D-list parts. Swanson wants to compare TikTok content creators to college students and thus denigrate video production as inherently inferior to the liberal arts. But the better comparison is to the ladder aspiring actors once climbed—the rounds of improv troupes and summer stock and gigs as extras. TikTok videos replace a lot of that mostly unseen work, and give young people a greater chance to break out, in public. Swanson himself notes that L.A. is always a magnet for young aspiring talent. But these collaborative TikTok and YouTube houses can't represent more than a few thousand kids at most, out of about 40 million in the 15-24 age bracket. I'd wager more teens work that old acting standby, as a restaurant server, than in TikTok houses. That’s not to say exploitation and abuse can’t or don’t occur in these houses—a recent sexual assault allegation against a YouTuber makes clear that they do. But the system, from the outside, doesn’t seem as bad as the historically exploitative acting industry it is attempting to replace.

So, sure, there are disturbing elements, as there are with any kind of work, but the young men Swanson profiles seem like the young men I knew decades ago. I don't think they are inherently different, and it's weird that he seems annoyed with and dismissive of their camaraderie, as though being nice, having fun, and enjoying life were signs that one has failed to achieve the rarified levels of self-loathing that mark the true artiste, the only worthy recipient of the divine gift of Art. He believes that the bonhomie is not just fake but a product of the evils of social media:

One thing that is so reliably upsetting about spending time with these social-media influencers is that they are all so garrulous and kind that for a minute you can’t help feel that they actually like you and enjoy having you around. The boys continue to refer to me by my on-court cognomen, Beanie Barrett, and they punctuate this endearment by enlisting me in several complicated handshakes, which makes me feel like a high school freshman. But it’s especially discomfiting to realize that the influencers have a tendency to treat virtually everyone in their social orbit with the same kind of backslapping effervescence with which they have treated me, and that this stems from their inexorable online habit of entreating their viewers to like and leave comments on all their social-media posts, not because they’re sincerely interested in what their followers have to say, but because this kind of “engagement” with their content is the sole barometer by which brands—i.e., their employers—determine their online relevance.

This genuinely bothered me because Swanson presents no evidence that these young men are faking their friendliness. It is entirely his cynicism, his inability to believe that people can be friendly even at the acquaintance level without an ulterior motive. It might equally—or more likely—be the case that content curation companies select friendly people to stock their houses.

If Swanson saw the same friendly, rambunctious behavior among the players on his college’s football team—as I did when I was young and knew many college athletes, most just as Swanson describes these young men—would it still strike him as false? If they were in a boy band instead of a TikTok house, would he still think them unworthy? Or, perhaps, might we suggest that losing the, if not intimacy, at least familiarity, between friends as we grow old and bitter and disillusioned isn't really the kind of maturity to celebrate?

People who are never angry are like dogs who never bark. Usually, there is something wrong with them which they learned to hide. It's not a coincidence that after another gruesome murder case we so often hear: he was very nice guy, rather silent and withdrawn, I've never hear him raise his voice etc.

Lead paragraphs: OUCH. >lol<