"You're Tearing Me Apart!"

A prose adaptation of "Rebel without a Cause" offers insight into the many ways Warner Bros. misunderstood their own film.

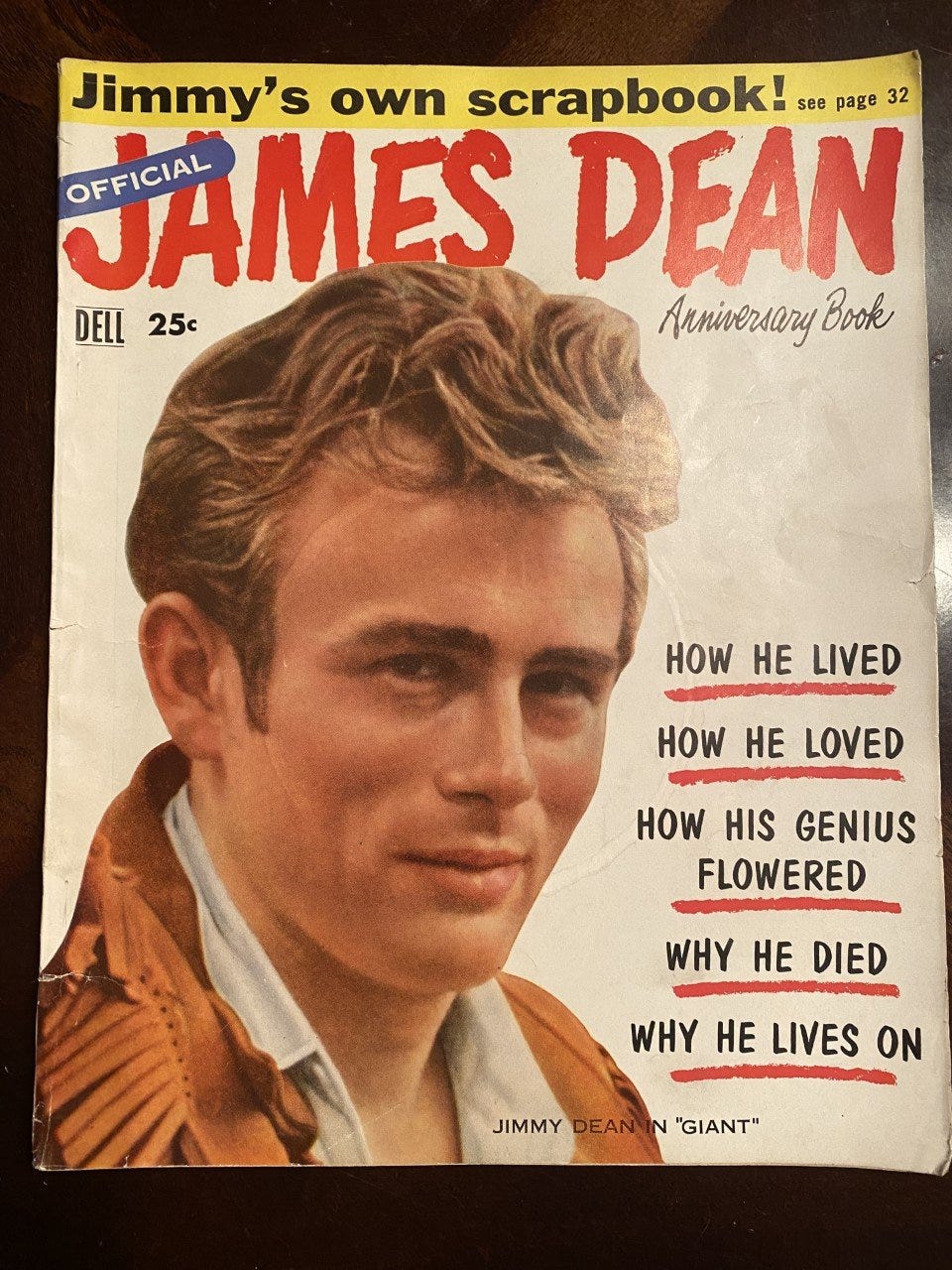

I didn’t think that after all the research I had done into James Dean and Rebel without a Cause for my book that there would be any surprises left. Then, on eBay I found a copy of the 1956 Dell James Dean Anniversary Book, a morbid magazine one-shot celebrating a year since Dean had died, for just $8. I was familiar with some of its content because it was a primary source used in many Dean biographies. I always prefer to use primary sources when possible, which is why I wanted to have it for reference, but I had assumed the standard authors had already mined it of all its useful material. I was wrong!

The Anniversary Book is a pretentious, overwrought bit of ephemera, filled with empurpled prose about “the earliest prophecies,” “that once a giant walked in our land,” and other such nonsense. It is patently obvious from the choice of subjects and interviewees that Warner Bros. publicity department had a heavy hand in shaping the content to promote Giant, then about to be released. Many of the anecdotes reported in the book are demonstrably false, though the reasons are obscure. Consistent efforts to misstate where Dean was between the fall of 1951 and the spring of 1953, when he was living off and on in a sexual relationship with another man, feel darkly intentional. Other blatant errors seem either due to indifference or WB’s promotional needs. Comparing the versions of the stories of Dean’s various girlfriends to later accounts is amusing, revealing how heavily actresses’ publicity needs shaped how close to Dean they pretended to be in the years after his death. Pairing this with a piece quoting Dean as saying all of the accounts published of him were “bullshit” seems almost like an editor amusing himself.

All of that, however, surprised me much less than a novelization (well, short story-ization) of Rebel without a Cause published “by popular demand” in the spring of 1956, about six months after the movie’s release, as part of a publicity campaign for Giant. The connection is obvious from the headline, describing Rebel as “the second of Jimmy Dean’s three great films”—clearly implying a third, Giant, was coming. The text had to be produced in cooperation with Warner Bros. since it is illustrated with studio-provided stills and uses dialogue from the film’s script—including lines from the script not found in the finished film. No movie magazine or major publisher would engage in wholesale copyright violation.

The story version follows the movie in a general way, but it simplifies the plot greatly. The opening scene at the police station is removed to a flashback, and the story opens with Jim getting ready for school. His mother sends him off with a “peanut butter and meatloaf” lunch (!), which at least Jim has the good sense to think gross. For some reason it is winter, likely a remnant of the original script, which was set at Christmas, not Easter as in the film. Similarly, in places where Dean improvised, the story preserves wording from the shooting script, so Jim tells Buzz he watches too much television here whereas in the film Dean improvised a line about reading too many comic books, playing off then-current Congressional comic book hearings.

The movie’s story is reduced to a conventional love triangle between Jim, Judy, and Buzz, while the character of Plato is almost wholly excised until the final paragraphs. The author greatly enhances Judy’s and Jim’s romance, giving them extra kisses not found in the film, and the story’s climax is presented as a nonsensical series of events. Jim and Judy arrive at the ruined mansion, but there is no idyl. Instead, Plato arrives with a gun, being chased by police for reasons never explained. The author seems uncertain in revising these scenes. Jim is “half-sobbing” over Plato but the author isn’t sure why, since Plato had no significant role and doesn’t quite justify Jim’s identification of him as “my friend.” In this version, it is already dawn and the police chase Plato to the planetarium, with Jim’s father, who meets up with Jim and gives him permission to enter the planetarium, over the objections of the police. The final scenes play out mostly as in the film, albeit unmotivated, with the gun and bullets and jacket, yet it uses a different ending shot for the movie but not used, in which Plato points the gun and Jim while on the roof and the police kill him to stop him from shooting. Plato plunges off the parapet to his death as Jim collapses—but doesn’t mourn or cry. However, the author has combined two endings, the scripted one and the one used in the final cut, so somehow this event takes place both on a parapet atop the Planetarium from which Plato could plunge and also on the front steps, where Judy could take Jim’s hand and walk off together.

This story is a curiosity to be sure, but it also testifies both to how radical Dean and director Nick Ray made Rebel without a Cause and how uncomfortable Warner Bros. was with its queer content. Given how explicit scriptwriter Stewart Stern was about Plato being, in his words, “a faggot” in his script, this can’t be attributed solely to a staff writer working blindly from a shooting script—though it’s clear the writer used it as a reference due to the difficulty in accessing film in those pre-DVD days. Excising as much of Plato as possible might make Jim a more robustly heterosexual hero, but it makes the story incoherent. Why exactly did Jim care so much about some rando he met once?

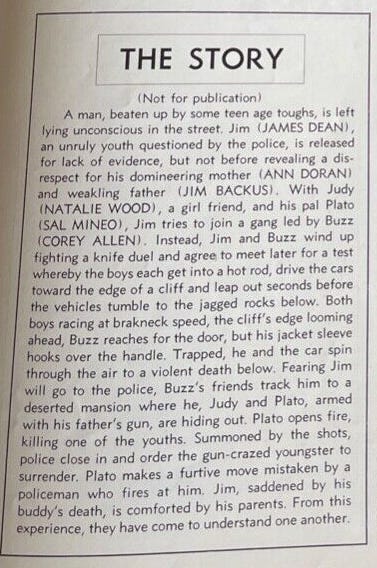

Nor was this the only WB revisionist take on Rebel. The official summary it handed out to reporters in its Rebel press book, working also from a draft script and not the finished film, removed all relationships from the plot and instead cast it as Jim’s effort to join Buzz’s gang, with Plato as a murderer, culminating in Jim and his parents coming “to understand one another.”

The difference is that the press book was written when WB wanted to promote Rebel as a “juvenile delinquency picture,” while the story version was written when WB was invested in promoting Dean as a (dead) heartthrob and object of desire.

It’s interesting to see how the same source script can produce such radically different interpretations according to the agenda of the people adapting it. And with printed texts shaping the cultural memory of films in the era when you couldn’t watch a movie whenever you wanted, it’s no wonder it took until the twenty-first century of so many critics to recognize that the on-screen story didn’t match the printed versions.