Creating a "Bisexual Psychopath"

Royston Ellis's working notes for his James Dean biography reveal the secret source who told him about Dean's same-sex relationships.

Recently, I wrote about some of the surprising claims that appeared in Royston Ellis’s 1962 biography of James Dean, Rebel, particularly those about Dean’s sexual relationships with men. His account, while imperfect, was mostly accurate and a more than a decade ahead of other authors. This week, I received copies of Ellis’s working notes for Rebel from the Harry Ransom Center of the University of Texas at Austin, and the papers shed light into how Ellis knew things he shouldn’t have known.

It was a little confusing tracing Ellis’s sources. First, his handwriting is terrible. Second, he worked in an odd way. He took notes about sources he read as he read them and then used scissors to cut the pages into strips, which he then pasted in the order he intended to use them in his book. As a result, since he did not plan to use citations, only some things carry their original labels, while most notes are unlabeled. Nevertheless, he coded some of the notes and included a key listing his (paltry) sources, which made it discovering what came from where manageable.

We’ll get to that in just a moment. First, the really weird stuff:

The working papers cleared up some other confusing claims that appear in Rebel. In the book, Ellis relates several stories about Dean freaking out after having sex with much older mother-substitutes. One of these stories involves a 14- or 15-year-old Dean being deflowered in the back of a car by an older woman who reveals that she has the same name as Dean’s dead mother, thus sending him into a tailspin. Another describes a 19- or 20-year-old Dean entering into sexual tutelage with a woman in her late 40s whom he calls “Mom.”

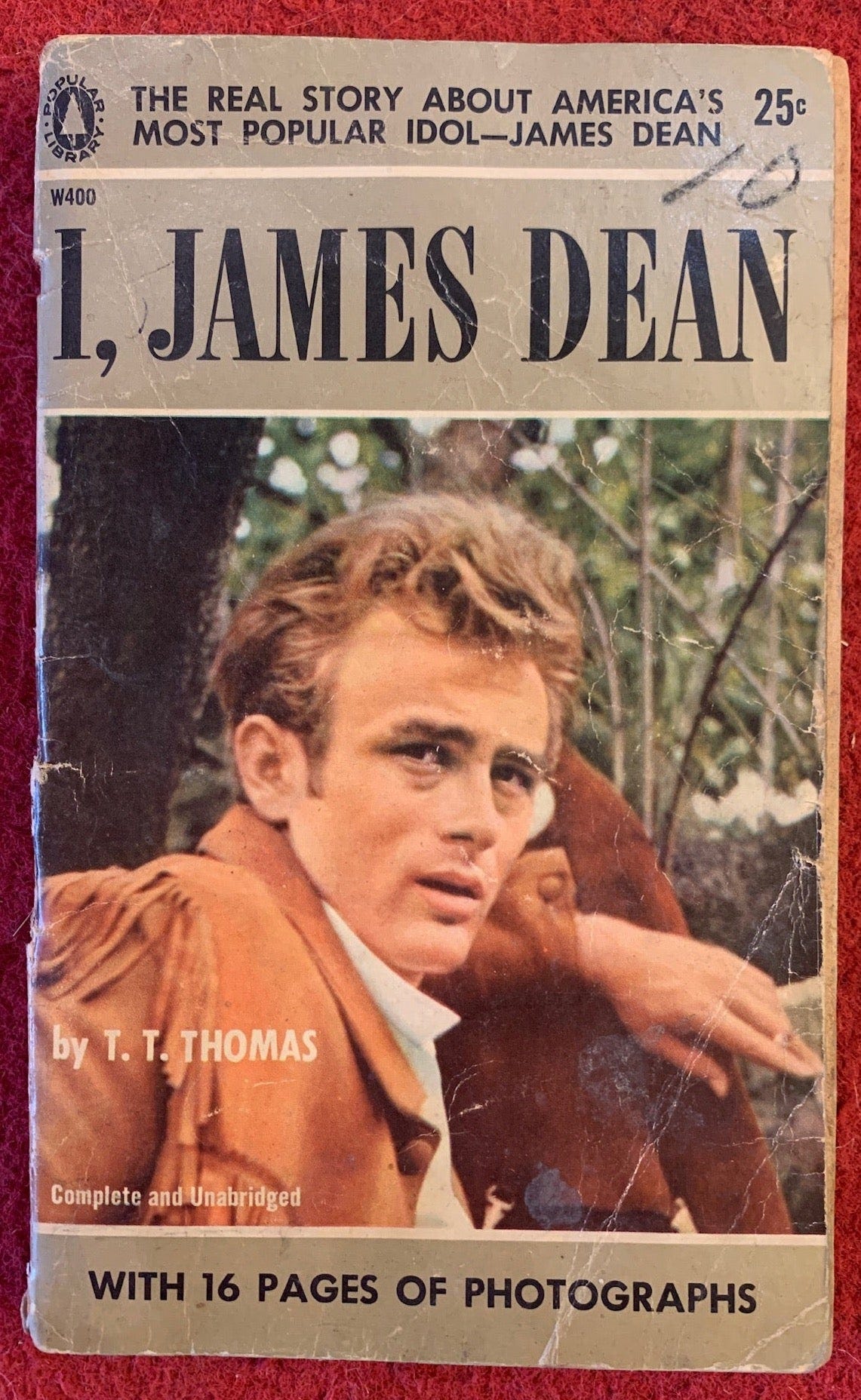

As I learned from Ellis’s notes, both stories came from a 1957 biography, I, James Dean, by T. T. Thomas. This book is almost never mentioned in any other source, save for an inaccurate description in The Unabridged James Dean and a misleading summary in Robert Tysl’s 1965 dissertation on Dean-themed media. The book is a lot weirder than any other author makes out.

I, James Dean is not what it seems. According to the U.S. Copyright Office’s registrations for 1957, the quicky biography put out by the Popular Library was actually the work of screenwriter and novelist Jay Dratler, best known for his Oscar-nominated screenplay for Laura (1944). At this point in his life, however, he was primarily a writer of erotic potboilers about such scintillating subjects as a doctor seducing his female patient or a trophy wife teaming up with a handsome young lawyer to off her husband. Dratler seemed to have a fascination with Freudian psychology and very few scruples.

I, James Dean is a stripped-down uncredited summary of William Bast’s 1956 Dean biography and Joe Hyams’s 1956 Redbook biographical essay, into which Dratler has inserted fabricated dialogue and imaginary testimony from Dean himself. Dratler’s thesis was that Dean spent his life trying to bed a mother-substitute until his overwhelming sexual desire for his mother resulted in a Freudian death wish that caused him to crash his car.

The (ridiculously) many middle-aged women Dean bedded after calling them “Mom” are obvious fabrications (with one racist one, finding Dean freaking out for violating “moral and racial laws”), and Dratler avoided any potential copyright problems by avoiding all genuine quotations from any person then living and using his screenwriting skills to invent conversations that never occurred, including some with people who did not exist. He avoided libel concerns with laughable little asides absolving living people of any blame and attributing unpleasant encounters Dean had to fictitious or unnamed people.

Ellis didn’t realize that the book was semi-fictionalized, so he wrongly assumed Dratler’s stories were true. This mistake had consequences, as we shall see.

As for Ellis’s discussion of Dean’s sexuality, it falls into two competing versions that Ellis wasn’t able to fully integrate. In Rebel, he separates each into its own section. The section on “Girls” takes its main ideas and themes, and much of its information, from Dratler, into which Ellis integrated material from a remarkably small number of sources. His notes list only six published sources, two of which were books (Bast’s and Dratler’s), and four of which were magazines. The section on “Sex” focused on men. Ellis’s notes say it was originally to be called “Homosexuality,” and his original conclusion was that Dean was gay and had always known and accepted what he was, but that his love for his mother led him to “sometimes” “chase girls.” However, unable to harmonize homosexuality with Dratler’s (fictitious) account of Dean’s MILF fetish, Ellis renamed the chapter first “Bisexuality” and finally “Sex.” He crossed out his original references to Dean being gay and replaced them with “bisexual psychopath,” for Dratler had labeled Dean “psychopathic” on page 88 of I, James Dean.

But Dratler hadn’t suggested Dean was anything but straight. He copied a section about predatory gays trying to seduce Dean from Joe Hyams’s Redbook piece and appended to it an apparently homophobic freakout over a director’s attempt to bed him taken straight from a 1957 issue of Rave magazine, a disreputable tabloid, in order to cast Dean as assertively straight and horrified by evil queers.

So where did Ellis get his notion that Dean was involved with men?

It turns out that he did not derive the information from a published source. Upon seeing Colin Wilson thanked in the book’s acknowledgements, I suspected Wilson might have been the source. In Surviving James Dean, William Bast, Dean’s best friend and onetime lover, recounted meeting Wilson in London in 1957 or so, and Wilson’s efforts to get information from him about Dean. “Colin pumped me endlessly on the subject, but [he] didn’t probe into delicate areas.” Writing at 60 years’ remove, Bast’s memory may have faded or perhaps he intentionally misrepresented the (sometimes drunken) conversations he had with Wilson over a period of weeks. But Royston Ellis’s notes record his conversation with Wilson in which Wilson told him point-blank that during these meetings, Bast told Wilson that Dean was “queer” and that Dean and Bast had been in a years-long relationship.

I would quote the material, but the University of Texas requires me to pay them for permission to do so, and I’m not going to pay them for a Substack post. If I’m spending money, it will be for my actual book.

Anyhow, while Ellis did not leave enough information to fully reconstruct his conversation with Wilson, it is evident that Wilson indicated how Ellis might read Bast’s book in light of this information. Bast must have shared with Wilson some information about incidents from Dean’s life that he had disguised in the book to hide homosexual experiences, since Ellis had some information that was known to Bast but not included in the 1956 James Dean biography. Thus, Ellis’s notes list a number of incidents keyed to Bast’s book and to the magazine one-shot The Real James Dean that are not specifically homosexual in the original but are read in light of Wilson’s account of Bast’s words and are thus interpreted (correctly!) in ways that would not be repeated in print until the middle 1970s. (He cites some to “personal knowledge.”) But Ellis, being overzealous, goes beyond specific incidents to create lists of behavioral traits (“got into tiffs with male friends, like a woman would”) that under his stereotypes about homosexuals suggest deviance.

Nevertheless, Ellis found himself unable to fully explain how James Dean could be both masculine and attracted to men. His notes express a desire to distinguish between “flapping queers” and “understanding boys”—between effeminate gay men and masculine-presenting men who had sex with men.

The long and short of it is that William Bast is a liar. OK, well, almost. Bast admitted to intentionally self-censoring his 1956 Dean biography to avoid mentioning homosexuality. He also spent decades dancing around the issue to “protect” Dean’s reputation from the stain of queerness. And yet, Ellis’s notes make plain that Bast told a different story in private, when he thought his words weren’t being recorded. He was the secret source for all the rumors that he himself expressed shock and horror at hearing and sought to refute!

The truly amazing part is how few people and how few sources shaped public perception of Dean for so long. I, James Dean is a mishmash of two earlier sources, Bast’s 1956 biography and Hyams’s Redbook article. Ellis’s book draws on each of these sources, and three more, but adds little to them. And yet, because the writers intentionally hid their sources and spoke out loudly against the very books and magazines they were drawing upon, when in the 1970s new biographies were published, the authors treated each of these sources as independent confirmation of various claims. But they were all repeating the same material, from the same source.

And weirdly enough, if Bill Bast hadn’t blabbed to Colin Wilson, who I would wager was probably also the source for the handful of Francophone writers mentioning Dean’s sexuality in 1957, Royston Ellis wouldn’t have written his homosexuality chapter, and the 1970s writers who cited him probably wouldn’t have gone in search of Dean’s queer side, and the old rumors would have faded into the background.

Just to add an observation. Dratler spent some considerable time in the Viennese demimonde, and could have hardly avoided the mania of the Freudian

Cult.

Bisexuality was not well understood then and would be seen as just a further mental derangement due to struggles with the confusion & self-denial of homosexual feelings.