Triumph of the Shrill

Jordan B. Peterson and Michael Shermer spend three self-congratulatory hours discussing Jesus, Nazis, and personal grievance

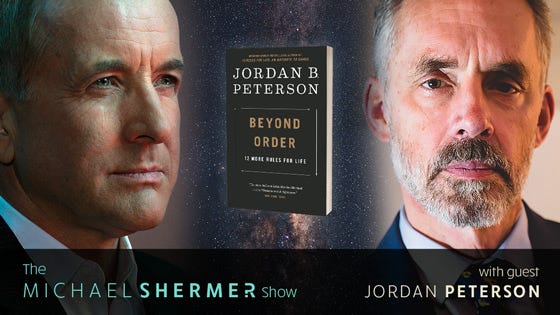

Controversial psychologist and lifestyle guru Jordan B. Peterson has a new book out, Beyond Order, in which he expands on his infamous rules for living with another dozen life lessons. The controversial Canadian academic supports his second rule, asking readers to aim single-mindedly at the person they want to become, with an appeal to ancient mythology, which he says is a guide to self-actualization. I read the book a few weeks ago, and I was dismayed by the way he misused mythology to create a bro-culture path to toxic masculinity with a Social Darwinist gloss.

In Beyond Order, Peterson misstates the content of the most important ancient text he cites, the Enuma Elish, which he sees not as Babylon’s version of a creation myth but as Mesopotamia’s one creation myth. He also misunderstands the culture that produced it. “Mesopotamians” are many different peoples, with many different beliefs, over many millennia, not one people. He wrongly claims that the text records the origin of monotheism, a weird belief popular with the people who helped give rise to Nazi Germany, and he is utterly unaware of competing versions of the story which undermine his ideas. Other cities beyond Babylon had their own creation myths with different gods in the central role. Yet he takes the story, and Babylonian efforts to incorporate gods from other cities into their own pantheon, as evidence that the ancients saw religion as a Darwinist competition between gods until one reigned as the monotheistic supreme deity, so therefore we should live our lives as a cruel competition for dominance. It’s all very weird and decidedly opposed to the actual texts, which were intended as syncretic, bringing together peoples and gods, not erasing them.

His scholarly shortcomings make plain how his toxic persona arises from ideology trumping evidence. Worse, his misuse of myth is self-evidently designed to appeal to his bro-culture audience of insecure men by crafting a false Darwinian survival-of-the-fittest narrative that can be dangerous if we see our lives as a zero-sum, winner-take-all game, something the ancients emphatically did not believe. He wants history to sanction ideology, when antiquity argues against him.

So imagine my surprise to find that Michael Shermer of Skeptic magazine released a three-hour podcast with Jordan this week in which they were to discuss “myth” and “the architecture of archetypes”—exactly the topics I find interesting. I was not looking forward to hearing how two men with very little understanding of ancient history and mythology between them would talk about mythology. It turns out that they mostly wanted to talk about Nazis, Jesus, and their personal grievances, all while imagining they were dispensing intellectual revelations about reality.

Peterson began by announcing that he is launching an app to teach writing, a skill for which he has, unsurprisingly, developed his own pseudoscientific model which he proclaims with much pomposity as a “Darwinian model” allowing for the “overproduction” of creativity followed by a “culling” process to achieve an evolutionarily defined balance. Regular writers call that a “first draft” followed by “revising and editing.” But leave it to Peterson to try to dress up traditional writing advice as a scientific breakthrough. Truthfully, Peterson is not a great prose stylist nor a particularly graceful writer, so I’m not sure what benefit customers will experience from turning themselves over to a man who says that most writers will be “catastrophic failures.” My, isn’t he inspirational?

I had never really listened to Peterson speak, and I had expected a dynamic presence to justify the hype. However, Peterson is not a particularly strong speaker, neither eloquent nor passionate, and I wonder what his followers see in him. Of course, we live in an impoverished age in which few public figures possess strong public speaking skills, except for preachers and con men. Hence, my expectations.

Between Shermer and Peterson, they name drop more public intellectuals in three hours than I have ever heard in an interview, as though they were competing to prove that their understanding of society has an intellectual pedigree beyond their personal preferences. The name-dropping rarely has much to do with the direct subject at hand, and many of their citations are to experts pontificating outside their field—Steven Pinker being the primary example.

As Shermer asks Peterson about literature and mythology, Peterson mines that depths of Joseph Campbell’s 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces and Carl Jung’s work on archetypes to imagine that every great story is a personalization of a universal monomyth held deep in our collective unconscious, calling tales of “man” overcoming adversity “instinctual.” Campbell’s work, while popular with the public, is not considered accurate or particularly rigorous in the academic, so naturally it is Peterson’s framework for understanding myth. He goes beyond Campbell and Jung, however, in arguing that myths are evolutionarily encoded into us so that following these stories provides a survival advantage because they conform to the contours of “the biology underlying all of that.” I almost want to credit him with trying to tie Campbell to David Lewis-Williams’s Mind in the Cave, but I don’t think he actually managed that trick, or else he’d have had to deal with the dismantling of “archetypes.”

If nothing else, Peterson is a man whose conversation is defined by a series of buzzwords and catchphrases he assembles in different combinations to drive home the same point repeatedly. He is particularly fond of “Darwinian,” “hierarchy,” and “instinctual”—all of which tell you something about his view of social organization. He obviously sees life a Social Darwinist competition for status. He explicitly says as much, arguing that such hierarchical instincts are “archaic” and cannot be sidestepped, though his analysis is belied by anthropology, which shows us that hierarchical social organization—particularly ascribed status—is neither universal nor, as best we can tell, the original state of humanity. “There aren’t any societies that you can find no matter how far you go back in history where you don’t see radically unequal distribution of resources,” Peterson says later in the show. He has, I guess, never met hunter-gatherers, many of whom have aggressively egalitarian social organization and distribution of resources. Michael Shermer tells Jordan Peterson that hunter-gatherer egalitarianism is a "myth" and they need rituals to force them to share resources because “they don’t want to share food” and there are too many “free-riders” and “cheats” who don’t pull their weight. “That’s the problem” with “compassion as a singular moral virtue,” Peterson responds, claiming that people are fundamentally selfish and will go on (essentially) welfare for a free meal unless society ruthlessly forces them to produce. I recall another rigorously hierarchical society that emphasized eliminating “useless eaters.”

Nevertheless, despite the existence of egalitarian societies (horizontally egalitarian at least—vertical have privileged status with resource equality), Peterson declares hierarchical social organization “universal” because Campbell identified fathers as “evil tyrants” who rule the world, while the “masculine” is defined as “order.” He apparently is unfamiliar with matriarchal societies. Similarly, he says that we personify the “state” as masculine and male because of instinctive masculine archetypes, which I suppose means that he isn’t aware of Mother Russia or that even America was originally personified as Columbia (a woman) before Uncle Sam.

A long section discusses claims that liberals and conservatives have different brain structures. I imagine there might be something to the idea of general tendencies toward openness to change affecting overall political preferences, but since what is “liberal” or “conservative” changes with the political winds, it’s hard to argue that political positions are defined by brain chemistry when those positions will flip with the next election. Peterson similarly tries to make the case for gender-based differences, and Shermer uses his own young son’s preference for male-coded toy choices as proof of “biological” differences between the sexes in terms of interests. Neither he nor Shermer seem terribly interested in exploring how cultural messages shape individuals’ choices, preferring to see biology separating the sexes, though to his credit, Peterson is slightly less rigid on this point than Shermer.

Both men believe that men are biologically driven to work harder jobs for longer hours than women, and Shermer says he can’t understand why women would want to be CEOs because the job is so hard. Peterson claims that being an executive requires “singular personalities,” and men have an “added advantage” because their biology drives them to want executive status. “Status confers upon males sexual attractiveness,” Peterson alleges, arguing that women prefer high-status men while men have no preference for a woman’s status. That might be true in our culture, but it is not a universal. I remind you that egalitarian societies have existed, as have matriarchal ones defined by the woman’s family and status. “It’s built in biologically,” Peterson says, with Shermer adding that men also want to jockey for position among their male peers. I should also point out that both men talk about men being driven to compete for women and to gain status vis-à-vis their "fellow males," but never once imagine men treating women as equals or as non-sexual friends. And, of course, Peterson undermines his own argument by using as his example his college roommate, who he says succumbed to the “socialization pressure” of a high-powered corporate job and changed his personality to match expectations. That is, I dare say, the opposite of an absolute biological imperative. It is quite literally proof of culture’s power.

After this, the two men try to play politician, and Peterson thinks he has stumbled on an amazing insight in realizing that many “countries” aren’t coherent political units. He lacks an understanding of the difference between state (the government), nation (a group of people with a real or imagined shared heritage), and territory (within or beyond official borders) and so surprises himself to discover that the borders “we” draw and the places “we” call countries don’t align nation, state, and territory. He doesn’t stop to realize that “we”—the West—drew those borders largely without the input of the people impacted, for reasons of colonialism, competition, and other corrupt ends. The men agree that the problem is collective ownership and that progress comes entirely through assigning property to individuals in order to ensure capitalists the power to monetize property. I have a Dawes Act to show them that might argue against individual land ownership being an automatic universal good.

A long section follows in which the two men try to discuss social issues, including the “Black family problem.” Peterson calls having children “brutal” while Shermer chuckles that having two incomes is “easier” so Blacks should get married, as though the recent need for two incomes to support a family due to corporate and government policies designed to stagnate wages for half a century weren’t responsible. There is nothing good that can be said here.

Next, Shermer brings up religion to rehearse old arguments about why the Resurrection narrative from the Gospels is almost certainly untrue by way of introducing a question about whether Christianity is meant to be mythically rather than historically true. Shermer’s literalism is frustrating as he tries to suggest he was the first person to imagine that the Gospels were intended as a mythic narrative and Christians have interpreted them “wrong” for two millennia. How one can be so old without encountering the wide variety of viewpoints expressed over the centuries, I cannot fathom. Peterson replies with Jung and Campbell, alleging that Campbell’s “hero myth” is “embedded” in our biology (it is not) and therefore these stories are natural and “inevitable,” so that all human values derive from an inherent internal narrative. That narrative didn’t really exist until Campbell invented it, but, sure, let’s all pretend that a story made up in 1949 is eternal and universal. To that end, he discusses the question of good and evil in Manichean terms derived from Christianity, which he in turn alleges are universal and encoded within us as some form of God and the Devil. But that just isn’t true. The Greeks, for example, did not view actions as morally good and evil the same way Christians did but instead operated on the notion of transgression and purification—they dealt with ethics, not with morality, and did not think of evil as Christians did. While it’s too complicated to discuss here, the point is that Peterson barely understands the subject he claims to pontificate expertly upon. He comes so close to understanding that he is really discussing Christianity—he acknowledges that Christianity is foundational in Western culture—but then takes a wrong turn and imagines that Christianity is the culmination of religious and spiritual development, the alpha and omega “transmitted orally across vast expanses of time” and the ideal psychological narrative for human development. He says that he found the Bible so profound that it is impossible to fully understand its depths, true beyond truth. We all saw that coming, right?

You will forgive me if I skip over their long discussion about religion, which goes close to nowhere. Jordan refuses to give an answer to Shermer’s question of whether the Resurrection actually happened, and he seems to be struggling to find a way to avoid making a clear factual statement, retreating to a quasi-spiritual notion that the Bible is the “greatest” literature and therefore the “greatest” truth. (He discounts Greco-Roman literature, incidentally, wrongly claiming that “all” Western literature derives from the Bible.) He makes some weird feints toward suggesting that humans are moving to make the miracles of mythology real.

Shermer and Peterson next discuss Nazism for half an hour or so with an eye toward proving that the German people were not persuaded by Hitler nor supportive of Nazi ideas. Peterson, to his credit, counters Shermer’s excuses with appeals to aesthetics and how Hitler used nonverbal, emotional, and aesthetic appeals more than logical ones. The power of Nazi aesthetics is a fascinating subject, but neither of these two have the framework or the breadth to discuss it coherently. (Shermer accidentally ends up calling Triumph of the Will an “incredible” film several times, which really calls for more qualification.) I’m not sure why they are so hung up on Nazis, but there are more productive topics.

I’m not fully comfortable with how easily Peterson moves from discussing Nazism to arguing that young men must be given permission to be “dangerous,” a he-man posture he contrasts with the effeminate loser state of being gentle and “harmless.” He calls teaching cooperation “a complete bloody lie” that needs to be stamped out among boys in favor of valorizing domination and aggression. Neither man seems quite to understand that they moved from criticizing The Triumph of the Will to cheering young men exercising that same will to power.

Then they talk about racism and attack anti-racists. Peterson claims it is a mythological ideology that “parasitizes” Campbell’s monomyth in service of “negative” perceptions of racism progress. Peterson and Shermer both argue that racism is not systemic, but instead is the result of a few bad actors, with Peterson adding that young people are searching for a “Romantic” narrative to give mythic weight to the “appalling” oppression they imagine exists. He tries to thread the needle, though, by claiming oppression exists but that we need to slow down and enjoy “incremental” change rather than push for a “Romantic” narrative about a need for major change. That sounds a lot like “sit down and shut up to me,” but what do I know?

Near the end of the podcast, Peterson discusses Existentialism in terms remarkably similar to Avi Loeb’s recent forays into finding the meaning of life in extraterrestrial existentialists, and I wonder why our public intellectuals are resurrecting 1950s philosophy.

Peterson and Shermer then engage in some bashing of liberals (or, at least, the “elite”) for their supposed “contempt” for the people they claim to help, and both agree that the “liberal elite” are unfairly attacking Peterson for his genius and for daring to speak to the hoi polloi instead of the elites.

I am concerned, though, that throughout the conversation both men can’t help but relate their analysis to their own biographies, seemingly attempting to universalize their own personal experiences as representative of the human condition. Since both come from similar middle class, privileged academic backgrounds (though a recent biography tried to cast him as a hardscrabble, rebellious James Dean type in rewriting his past), it feels like they would benefit from imagining the world beyond themselves. I share three quarters of the same background, and even with that much similarity, I felt far afield from their assumptions, particularly since, as a gay man, I don’t get to stand on the side of the fence that can chuckle that the minorities just need to work harder and act more like straight white upper-class men to succeed.

Kudos on your commentary on JP. Beware the younger set, especially the "Proud Boy" sort genuflect before JP as their new godling. I've never been impressed with gurus, and Jordan Petersen confirms my bias. This modest but competent professor rocketed to rock star status simply because he picked a fight with feminists on campus resulting in many anti-feminists, manly men and boyish incels worshiping JP. They think they have discovered depth when much of his spiel is simply good old fashioned common sense. He writes such advice as "stand up straight", "don't lie" and "pet cats". I can endorse such teachings but I will not fork over $ 30 for a book based on the sort of things that Grandpa will tell you for free. Good work !

Colavito frequently asserts that if another writer doesn’t mention all opposing ideas they are “completely unaware” of them. He also complains that if other writers don’t mention what all other cultures think that they are biased. This is amateurish and biased nonsense.