"Tu Felix Austria Nube"

Netflix's "The Empress" tries to be a Habsburg version of "The Crown" by way of "The O.C." It succeeds despite itself.

Bella gerant alii, tu felix Austria nube

let others wage war; thou, happy Austria, marry

In Europe, this was the season of Sisi. In an odd coincidence, a number of major media projects focusing on Elizabeth, Empress of Austria debuted within months of one another on the Continent, including two television series, a movie, and (in the coming weeks) a novel. Over on this side of the Atlantic, only one has seen widespread distribution, Netflix’s German biographical series The Empress, perhaps the loosest and most upbeat of the set. When I saw this listed on Netflix, I was rather intrigued; regular readers will recall that Habsburg history is one of my great interests, and rarely does it receive the kind of lush dramatic treatment that Netflix usually reserves for British royalty.

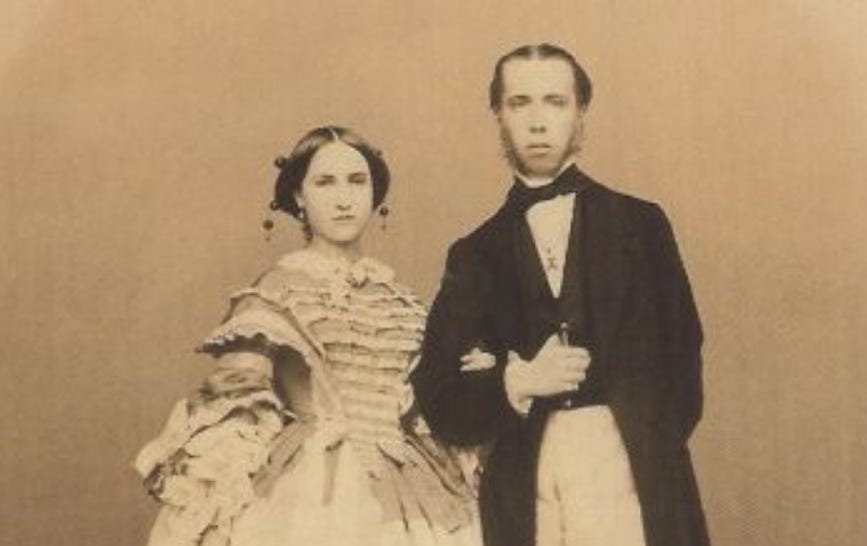

Despite the show’s title, the six-episode first season is about equally divided between Elizabeth and her husband, the Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria. The show covers a little more than a year, from 1854 to 1855. It tells the story of the imperial couple’s courtship, Elizabeth’s struggle to take on her imperial role, and Franz Joseph’s handling of the Crimean War, concluding with the conception of the couple’s first daughter, the ill-fated Archduchess Sophie.

The Empress looks beautiful. Although the production did not shoot at the actual Schönbrunn Palace outside Vienna, the castle they used was a reasonably grand facsimile, and the production design accurately reflected the grandeur and gilding of imperial life, correctly replicating a number of small details, from the double-headed eagles festooning the Habsburg court to the spartan iron military cot the emperor insisted on sleeping on instead of a full-sized bed. Unfortunately, the production design is infested with the current craze for a teal-and-gold color palette, so every room in every location is teal, even though the real Habsburgs tended to festoon their spaces in ungodly amounts of saturated red.

Netflix makes an understandable choice in casting two disconcertingly handsome actors as the Emperor and Archduke, Philip Froissant as Franz Joseph and Johannes Nussbaum as Maximilian, each quite a bit more attractive and ripped than the underweight young men with droopy Habsburg lips they portray. Less understandable was pairing two preternaturally golden imperial brothers with Devrim Lingnau, styled naturalistically as Elizabeth and, while certainly attractive, not given the same CW-style teen drama styling and gloss applied to the boys. Frankly, in many scenes she looks dowdy with understated makeup and unflattering hair, as though arriving in Riverdale from The Crown. At times, the lack of polish applied to the title role threatens to make her a supporting character in her own story. It is all the stranger since the real Elizabeth was famous for her styling and fashion.

Two major conflicts drive the action, one true to life, the other largely ahistorical. The conflict rooted in real history was the power struggle between Elizabeth and her mother-in-law, the elder Archduchess Sophie, who fancied herself the true power in Austria. This really happened, much as depicted in the show. The second conflict, between Franz Joseph and his brother, the Archduke Maximillian, has a kernel of truth—Maximilian was much more liberal than his brother and clashed with him over reforms—but the producers turn the bookish polymath Maximilian into a wild, hard-partying bad-boy rogue, with a crazy fashion sense and a Trumpian desire to plot a coup. Nussbaum’s Maximilian is a great character, but not much of a historical figure. Similarly, the show tries to make the stolid, dutiful, dull Franz Joseph into a passionate romantic lead, an effort that runs aground as historical fact repeatedly crashes into revisionist characterization.

The Empress tries is best to make the audience see Franz Joseph’s pairing with Elizabeth as a sexy, grand romance undone by the needs of state, but to do so it glosses over uncomfortable truths. It does not tell audience, for example, that Elizabeth was fifteen when Franz Joseph passed over her sister to propose marriage and sixteen when she wed the then-23-year-old monarch. Lingnau is 24 and looks a full-grown woman. Her sex scenes with the 28-year-old Froissant, with plenty of explicit nudity, are, if taken literally, simulated child pornography.

If you can look past that, as all viewers of CW-style teen dramas do with their twentysomething “teens,” The Empress is an enjoyable if inaccurate romp through a small slice of Austrian history. Viewers unfamiliar with the intricacies of Mitteleuropa in the middle nineteenth century will likely be quite confused by the show’s political stories, which fail to educate viewers on the Habsburg Empire, its government, or the Crimean War raging beyond its borders. Viewers hoping for a Germanic The Crown will similarly be disappointed in a show that can’t see beyond nuclear imperial family. A better show would have made use of the ex-Emperor Ferdinand, the King of Bohemia, much the way The Crown made use of the ex-king, the Duke of Windsor, in its inaugural season.

Ultimately, The Empress feels a story attached to the wrong people. While plenty could be said about the way the show intentionally makes Franz Joseph and Maximilian into analogues of Britain’s William and Harry, or Elizabeth into a rather explicit prophecy of Princess Diana (that overwrought final scene!), much of the characterization of the imperial brothers seems to have been borrowed from Franz Joseph’s son, the Crown Prince Rudolf, and his close friend and cousin, the Archduke John Salvator. In them we find the wild parties, the seduction and womanizing, and in Rudolf the liberal instincts and the rumors of a coup to overthrow Franz Joseph to save the empire. It is in Rudolf we find the charisma and the self-doubt the show tries to visit on Franz Joseph—a man who in real life, upon visiting the Great Pyramid, had no other reaction than to complain that the guides didn’t button their shirts. Rudolf, by contrast, chased jackals up and down its stones and rhapsodized over its ancient wonder.

The Empress is telling a thematic story that would have worked better with Rudolf and his failed marriage, but in today’s world, his unseemly end—murdering his teenage lover before killing himself—wouldn’t play well, so his more interesting traits have been visited on his father and uncle. It is apparently more acceptable to watch a grown man have sex with a teenager if you marry her instead.